Adrian Read is one of the unsung protagonists of the…

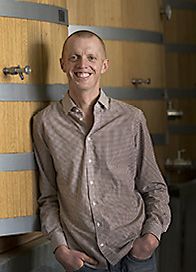

Chris Ringland : Flying Winemaker

I’d have to agree with Nick Ryan when he described the masterclass featuring two of Australia’s most reclusive but collectable winemakers, Chris Ringland and Drew Noon, as evidence of the bespoke nature of Tasting Australia’s wine master classes.

I met up with Drew not long after this event, and I was lucky enough to join Chris at a very small private tasting he held at his home recently.

Wine of the TA Master Class for me was Chris’s Spanish Alto Moncato Granacha, as good as anything I have tried in Spain.

I have developed a keen interest in Spanish wines as my son Sam lives in Madrid.

We visit he and his wife Bea most years. Even bought a couple of bottles of the Alto Moncato to take back to Spain to share.

Chris spent many years working with Robert O’Callaghan at Rockford.

Internationally he’s very well known for one his earlier wines ‘Three Rivers’.

To quote James Halliday

“The wines made by Chris Ringland for his eponymous brand were at the very forefront of the surge of rich, old-vine Barossa shiraz discovered by Robert Parker in the 1980s. As a consequence of very limited production, and high quality (albeit polarising) wine, it assumed immediate icon status.”

I’m not always a great fan of what are loosely called big wines, but I’d have to say I have enjoyed what Chris calls …”big, strong wines that age well”.

Here’s an email I received the other day from Sarah Ahmed, The Wine Detective. looks like she agrees.

Tasting Australia the ‘Master Class’ how was it for you ?

Nick Stock was the one that launched the idea.

Obviously, it was pretty bloody brilliant to be asked to do it, but it was vintage, so we had zero chance of getting together before the night other than a couple of brief phone calls.

I remember Drew suggested in one of the phone calls doing a bit of a mutual focus on vintage.

So, it just evolved from there.

I chose the wines that I wanted to present based on knowing a bit of the story about the various things that I do and had been doing.

There was always going to be a reference back to the Rockford influence and there was a chance to show a bit of the Spanish work which essentially gave me a chance to say that that Spanish work wouldn’t be what it is without Robert.

It was my first chance to have a really good chat with Drew for more than 10 years.

We agreed we’d tell a bit of a story about our wine path, the influences we’ve had which have resulted in the distinctive characteristics of the wines we’ve been producing.

I must admit, I think, the group of people that attended were a pretty interesting group of people and for me it was excellent.

Normally, I don’t get involved with stuff like that, but Nick Stock basically said, “Chris, I think, you should do this”.

I get the feeling that Drew thought it was very worthwhile as well.

Wine of the night for me and many others was the Spanish ‘Alto Moncato’ Granacha 2013 : what’s the back label ?

In 2001 a bloke named Jorge Ordóñez’, an American wine broker rang me up and said, would you be interested in exploring some new projects in Spain ?

At that stage I’d been working in Italy for a few years.

Jorge’s still very important, one of the first generation of importers of unique independent Spanish Bodegas into the United States.

Things were just going crazy, you know, the US had this amazing love affair with what was happening in Australia, but Spain was just really kicking it.

So I thought, this is pretty damn exciting.

He said, “look we’ll need a couple of weeks to travel around looking at different regions”.

And I said, “Based on my Italian experience, it’s all about the vineyards. Now if we go to a region and meet people, and find that the vineyards are all right, you’ll know that it’s going to be a no-brainer to develop a project.”

So essentially, we zeroed in on regions of Spain that tended to be overlooked, and a little bit of second-tier regions that Jorge believed had enormous potential but needed a little bit of TLC and attention to detail to bring them up to the next level.

That’s where it all started.

I then started to structure my annual work arrangements at Rockford to make sure that I could actually go away for a couple of weeks at certain times of the year and make sure that the work at Rockford was uninterrupted.

Grenache vineyard in Pozuelo, Borja sub-region. Campo de Borja, Spain, June 2002 : Photo © Chris Ringland.

That required just a bit of good prior planning and to my delight it worked.

For me, when you get given an amazing opportunity, you take a bloody big bite and then chew like crazy.

Chris Ringland consulting with José Miguel Sanmartin, José Luis Chueca, and Alberto Sebastian. Campo de Borja, Spain, June 2002 Tabuenca Sub-Region.

I think, the reason that we realised that these Spanish projects were going to work was because, right from the beginning, I decided the winemaking had to be essentially a slightly modified re-creation of the simple winemaking we practiced at Rockford.

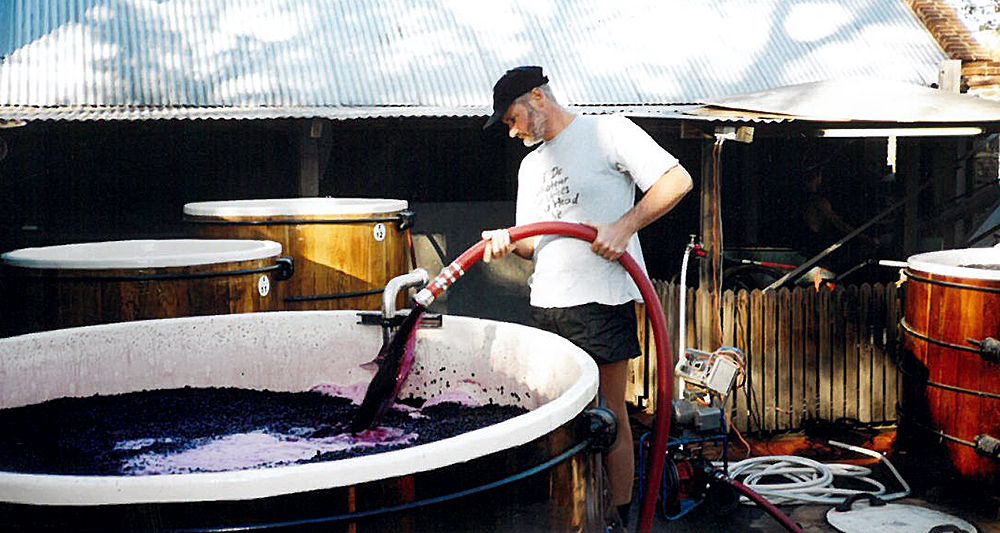

Individual vineyards were kept separate, simple winemaking, shallow ferments, out in the open air more often than not, basket press, keeping it simple.

With the Spanish projects, because there was a big problem around 20 years ago with brettanomyces and diseased old wood, we decided that while we were getting the projects up and running we would actually build new standalone Bodegas, or wineries.

We decided right from the beginning to use nothing but 100% new oak, much of it from AP John in the Barossa, so we didn’t inherit any of the disease.

Now it’s a pretty expensive and lavish approach.

Luckily we had some very good backers who were prepared to fund it.

I did start to see a little bit of pain on behalf of the investors when after a few years we were getting to that point where we were about to start releasing wine.

But we were still spending a lot of money making wine.

That’s the breakthrough point with any project.

Where it’s either going to fall apart and everyone’s going to say it’s too hard, or they’ve got the resources and the metal to push it.

I had had some great Advocate reviews.

But I wasn’t deliberately making a formulated Parker wine. was, if anything, actually making (dare to say it) a formulated Rockford wine.

That was all about just bringing the best out of the fruit with simple approaches.

It all started back in 2001.

I’m now a partner and consultant to Bodegas Alto Moncayo and delighted to now be able to offer small allocations of these wines in Australia.

I’m glad you and the others enjoyed the 2013 ‘Alto Moncato’ Garnacha.

Imported wood from AP John ?

AP John, the factory floor : Photo © Milton Wordley.

That was one of the foundation aspects, I said,

“We’re going to use these little cube stainless steel fermenters so we’re going to have to get this going fast, so we’re getting them made in Nuriootpa, stuck in containers, shipped to Spain and we’re going to fill those containers also with new AP John American oak.”

The Spanish guys were attracted to the idea because they really loved the idea of starting a project with oak that nobody had heard of and nobody could get.

To the extent where when the barrels arrived in Spain, they employed a cellar hand to actually shave or sand the AP John logo off all of the barrels because they were paranoid that other people would see and try and make contact as well.

It was wonderful and, of course, the barrels worked beautifully in a way that, in fact, I would never have utilised them with Barossa Grenache.

The power of a lot of that mountain grown Spanish fruit is incredible.

Three years down the track, when we were ready to launch the wines, to my obvious delight they looked pretty damn good and it was all, at that stage, totally for US importation and distribution.

Another wine I enjoyed that night the Solita Nebbiolo quite a different beast to a Barossa Shiraz.

The Solita is also Nick Stock’s fault.

In 2003, he contacted me, wanting to get involved with a Nebbiolo project.

I think what made me immediately say “Yeah, I want to do this” was because Nebbiolo is just so different than Shiraz.

My role with Shiraz is to gently coax its existing personality out and preserve it, whereas Nebbiolo is almost the opposite.

Nebbiolo requires the winemaker to do some unusual things sometimes.

I just figured that the complexity of a spontaneous fermentation would add extra layers to the Nebbiolo fruit personality, and that would pay you back down the track.

And it bloody well worked. It was never going to be a big project, a tonne, and a half, a combination of the five different clones that were planted, selected from a specific part of the hillside.

A week before we planned to harvest.

I went down and filled a plastic bucket with Nebbiolo fruit, bought it home, hand de-stemmed and crushed in the kitchen, put a tea towel over it and let it sit in the kitchen to start fermenting by itself.

Then I used that actively fermenting bucket that had been sitting in my kitchen for a week to actually innoculate the ferment I wanted to make a bit of a modern Nebbiolo style, so I decided to use a new French oak large Demi-muid (600L) barrel.

The ‘Solita’ at the Mercato ‘Cin Cin Nebbiolo’ Master Class with Tony Love and David Ridge at Mount Lofty House : Photo © Milton Wordley

I didn’t want to make a copy of an Italian wine, I wanted to make a wine that actually says something about Australia or about the environment that it comes from.

The Solita is normally released as a 10 year old wine, the Nebbiolo fruit is sourced from the Longview vineyard, near Macclesfield, in the Adelaide Hills.

The vineyard was established by Duncan MacGillivray in the early 90’s and is now owned by the Saturno family.

Early life and why wine ?

I grew up in Auckland with a Danish Mum and an Irish Dad – both sides had immigrated to New Zealand around the time of World War II.

Among the fellow Kiwis at Chris’s first year at Roseworthy was Michael Brajkovich MW of Kumeu River wines : Photo © Milton Wordley.

On special occasions when the family got together, wine and beer were fundamentally important.

Funnily enough, when I was a little kid, I was fascinated by the whole label thing at first.

I thought they were just amazing.

When I was 14 we did a school holiday experiment. My neighbours had a plum tree that was totally loaded with plums.

I’d been doing a little bit of reading and I decided with a couple of school mates to make a bit of plum wine and it came out rather well.

I thought, this is certainly an interesting and rewarding hobby and there were no complaints coming from the parents in regards to having a glass of homemade plum wine.

I got really interested in it and started reading some of the old, mainly English, home winemaking books.

At school we were studying science, chemistry, and biology and I wanted to know how it all worked.

I continued to make batches of wine at home with the help from my school mates, I was 15 at the time and had started to read some of the bulletins that were published by the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research on winemaking.

I got talking to some of the scientists there about what I was doing at home.

One of them basically suggested to me, you know that, if and when you graduate, you can go and study winemaking. I applied and was accepted into Roseworthy as a full-time student for the commencement of the 1979 academic year.

Before going over the South Australia, I worked for a year in a pickle factory and did a deal with my Mum and Dad, who said that, for every dollar I saved, they’d match it.

So off I went to Roseworthy in 1979.

It was an amazing group that year, even had some other Kiwis there Michael Brajkovich, Rosie Butler, John Mushet.

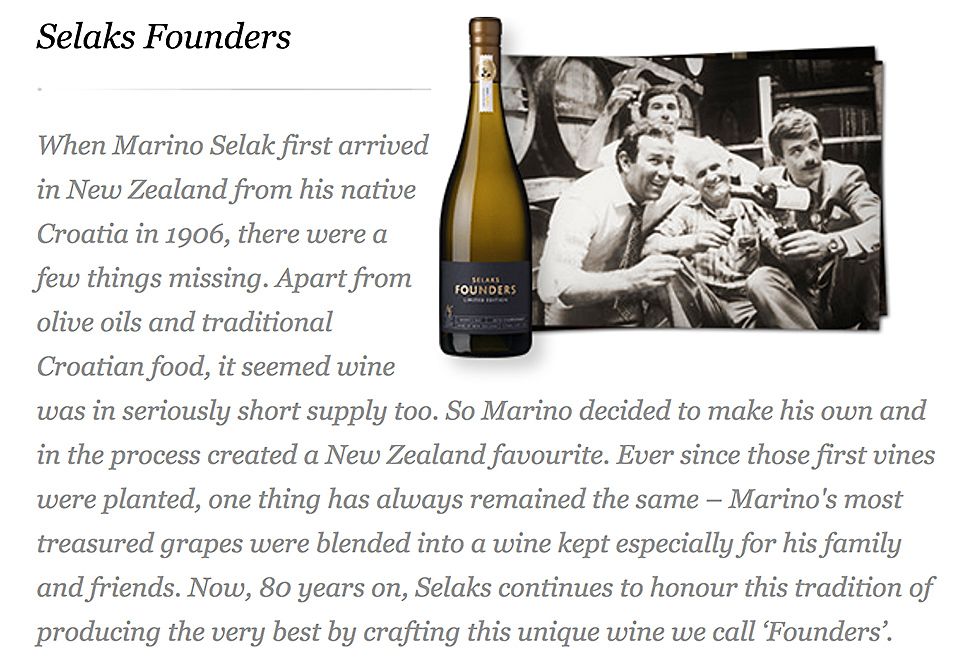

After graduating I went back to NZ for a while and worked at Selak’s in Kumeu.

How did you come to be in the Barossa ?

When I was at Roseworthy, the Barossa was considered a joke, it was a dinosaur.

I remember lecturers like Richard Smart joking that the Barossa would probably not exist as a winemaking region within the next 20 years, what with the cool climate viticulture, and the beginnings of the climate change debate.

To me it’s so interesting to look back and go“Well that didn’t work did it!”

The Barossa really has, sort of, got its act together and asserted itself.

Around 1986 I was back in NZ, I’d started travelling and doing a bit of, dare I say it, the flying winemaker thing, which was just starting to kick in.

I came back to South Australia.

Mark Turnbull offered me a cellar position at Saltrams for the 1986 vintage.

I also did vintages in California.

My plan back then was just to bounce backwards and forwards. It was after the second bounce-back at Saltram that the connection developed with Robert O’Callaghan.

I lived on Krondorf Road and got to know Robert very well. Rockford was just starting and I’d often call in on Robert on my way home.

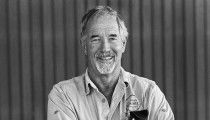

Rockford and Robert O’Callaghan ?

For me, you know, there’s an awful lot about my winemaking that came from the grounding I got from working with Robert.

I started with Robert in 1988 as cellar hand/general dogsbody.

When I look back now the reason I think it was also successful was because all of the potential competition at the time discounted Rockford because they thought it was a bloody joke.

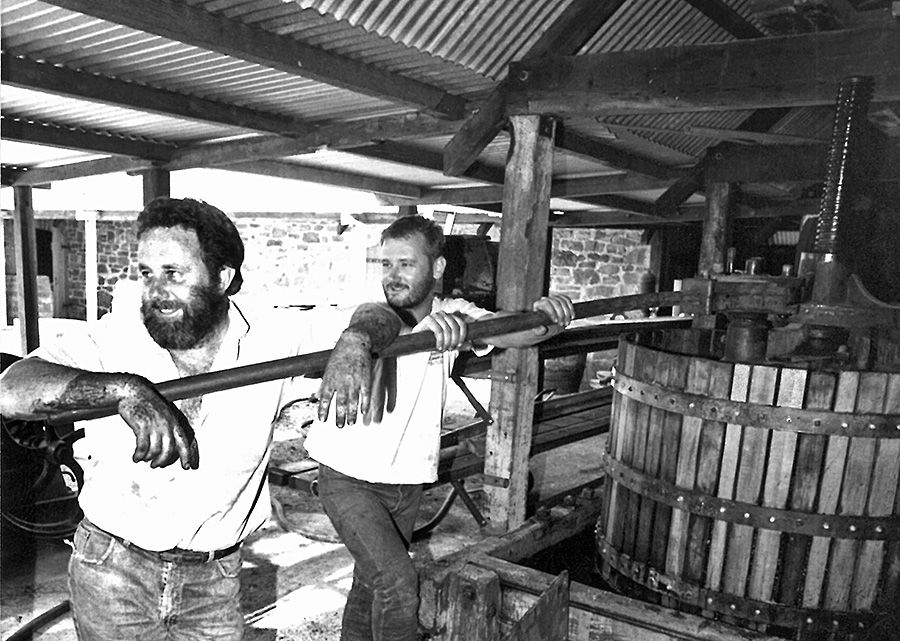

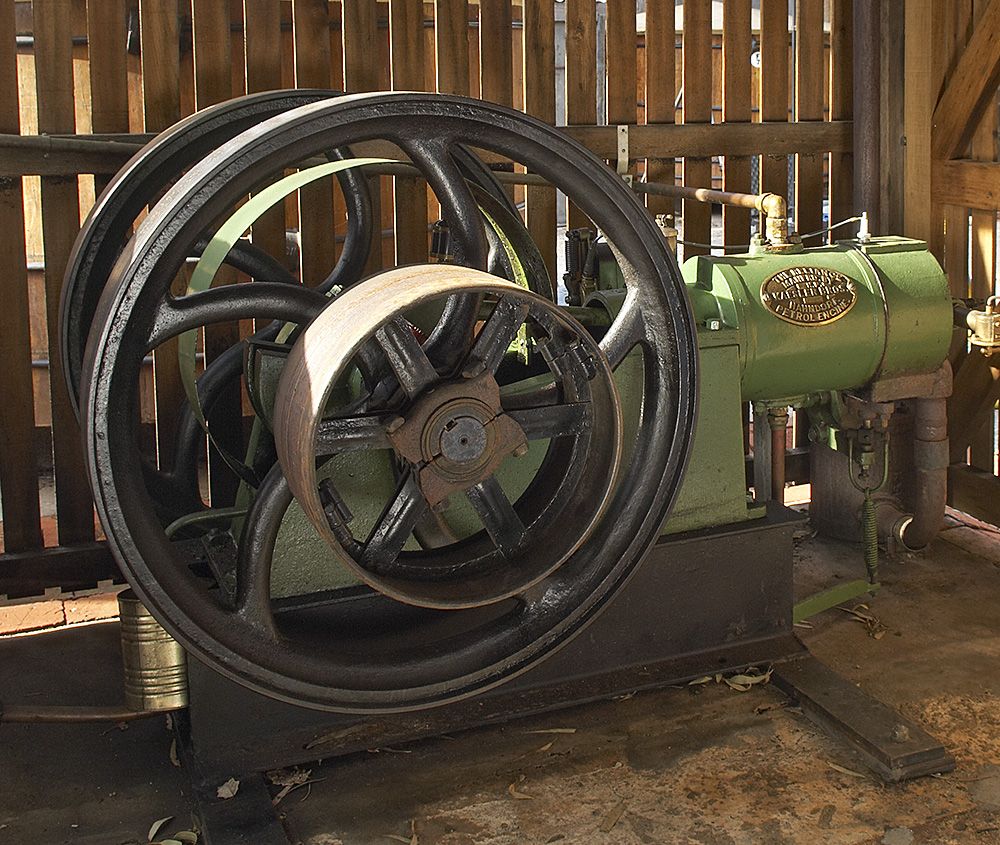

It was a classic ‘Method in the Madness’ that everybody at the time thought, why are you running a winery with a single cylinder petrol engine with a rescued wooden crusher and again, a Robinson press that had probably been lying on its side in a paddock somewhere in Rutherglen.

It was all done with quite careful budgeting really, there was not a lot of financial resource, but it taught me to appreciate the simple little things straight away.

Things like using a re-conditioned 2000 litre dairy chiller to chill the must.

It was highly labour intensive with simple operations and the wines really turned out bloody amazing.

I like to think that accurate recording keeping was the contribution that I made right from the start when I was in charge of the day-to-day looking after the wines, the barrel work and the blending.

Rob taught me strict protocols for the way barrels were looked after and there were aspects of that which were also quite against the current thinking at the time – not topping barrels, not unnecessarily opening barrels to sample them.

Robert O’Callaghan, Rockford wines : Photo © Milton Wordley

I was the barrel sampling Nazi, not even Robert was allowed to show anybody a barrel without my permission.

My protocol included using the sulphurtometer to make sure that we kept the SO2 levels properly maintained, sulphur in the head space was to soak up any oxygen that had entered when you open the barrel, but also inadvertently, of course.

We were preventing the proliferation of VA and other problems.

These are all simple, old fashioned techniques that Robert had actually translated from his early days at Seppelts in Great Western.

I had the fancy winemaking education and Degree, but I was not stupid enough to go against someone whose got experience and uses a series of simple procedures.

Just do it – don’t say I can do this better, just stick with it.

We made some great wine at Rockford.

While you were there you started Three Rivers ?

In 1989 there was an opportunity to do a little side-line winemaking project.

Rolf Binder, a mutual friend, actually engineered it together with Jane Ferrari who was also another Roseworthy classmate.

Rolf was the one that brought us together and Rolf was the one that gave the connection with the parcel of fruit at Marananga from Malcolm Seppelt – that vineyard is now owned by Torbreck.

Rob had given me permission to get involved, he said,

“no more than 2 tonne, it can’t interfere with your day job or you’re in trouble.”

So we decided to do it as a little side-line project.

Rolf had a little fermenter so we did it after hours at Rolf’s place, pooled our resources and bought some pretty tidy new oak from AP John.

That’s where the AP John relationship started off and it just developed from there.

A lot of my colleagues were quite critical saying,

“ this is 15.3% alcohol, what are you making, Port ? ”

I think shallow, warm, open fermentation certainly is a major key to developing harmony and integration, especially with a red ferment because you don’t have reflux happening like you would have when you’re doing a ferment in a closed tank.

That’s one of the things that maybe would contribute to port-like jammy notes, I think, that’s one of the factors and that’s why, I think it’s all about shallow, open fermentation and not being fussy about temperature – let them get quite hot.

To my astonishment, the wine started to get an international profile when Robert Parker gave the 1993 vintage, 99 plus – that created a huge surge of interest…not the least because there were a whole lot of people in Australia that had never heard of this wine.

I made Three Rivers Shiraz for six years from the 1989 to 1994 vintage.

I was advised earlier on by my accountant to get my act together with trademarking so even though in the early years I sold the bulk of it to customers in Melbourne I undertook the trademark of Three Rivers worldwide.

The last region to apply for a trademark was the United States and that was the first region to result in a dispute.

I sold them the worldwide trademark for quite a substantial sum and so it was a win-win, once the story got out about how it evolved, Robert Parker in particular was incredibly supportive because for years after that he always referred to the wine as Chris Ringland, formally Three Rivers.

I got to sell the trademark and keep it, in a way that it was not possible they could challenge.

For me that was an early, very important learning curve, when you start a little winemaking project, get your IP organized, because if something becomes successful, IP is the thing that people try to erode and snatch from you.

Robert Parker has given your wines very high points and once wrote “…the greatest Shiraz made in Australia”. How was it living up to that a few years ago ?

When it happened I ignored it.

I think, a lot of other people in the Australian industry were actually quite perplexed because a lot of people probably would have used it as an opportunity to organise a major town parade.

I completely ignored it. I kept it very quiet and discreet.

For me it was simply, sorry, Robert another lesson that you taught me – develop the relationship with your customers – it’s your customers that are going to be writing the cheques and handing over the cash to keep you from starving.

So I just kept the relationship going with the customers and kept it relatively low key.

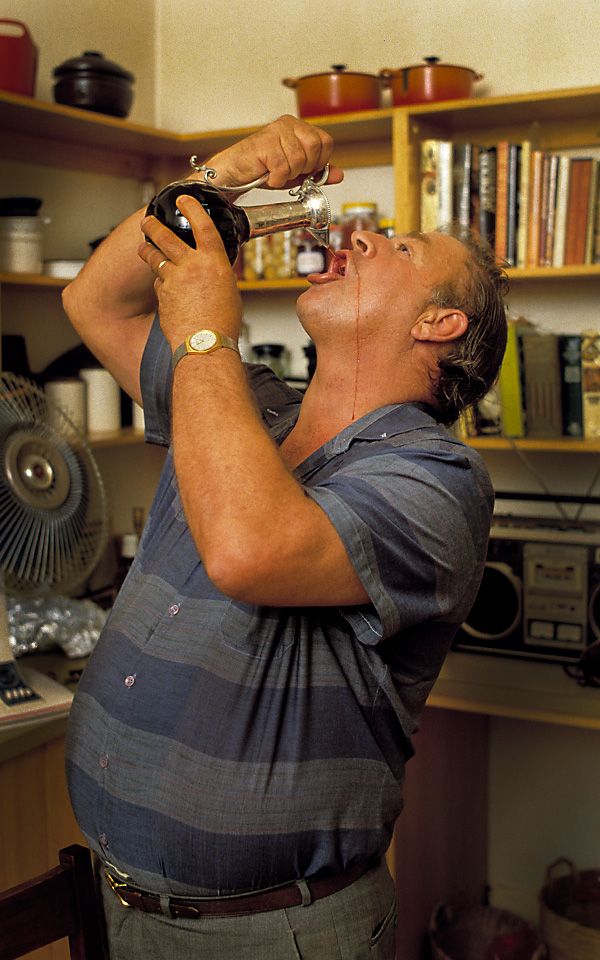

If you are lucky you’ll get an invite to a small private tatsing at Chris’ Eden valley home. It’s all about keeping a great relationship with your customers. : Milton © Wordley.

Probably the biggest thing that I found out which needed to be managed, is the tendency for people to believe that there is this ‘Parkerisation’.

Or that there is a certain type of wine or style of Parker wine.

Having met Robert on several occasions and tasted wine with him, the opposite is the case.

Robert was all about just lauding wines that were harmonious.

He’s a really good guy to taste wine with, he’s so down-to-earth and when it’s good, you can tell, he’s not like one of those poker players.

So in Layman’s Terms, what style of wine are you making ?

I like to make big, strong wines that age well.

I think the combination of the techniques of harvesting the fruit quite ripe, gentle vinification – simplicity in the early winemaking; maturation without messing around with the wine, leaving it alone, just letting it develop its own time.

It’s what I call drinkable.

Another Rockford thing was making sure the fruit was properly ripe, Shiraz does need to get ripe and that’s because you get more colour, the tannins soften, and then you get evolution of flavour into these more generous complex flavours that do seem to age really well.

You know, for me I like Shiraz for long-term ageing, but if that doesn’t work for you, , it’s okay if you want to make a young, fresh, early drinking wine but, I think, as a winemaker it’s like anything, say as a musician or an artist or anybody, you have to establish a style that you’re going to focus on.

If you start poking around and drifting around, I think, it sends a message that you don’t really have any conviction about what you’re wanting to achieve.

I was powerfully influenced by those early experiences, those beautiful wines Peter Lehmann made.

Robert pulling out beautiful old Wendourees to try when we were having a staff get together.

Your current business set up ?

I’m involved in various ventures here in the Barossa and elsewhere < chrisringland.com >

Many of them involving Nathan Burley and Adrian Hoffmann.

The Hoffmann family started selling grapes to Rockford in 1992.

That’s when I first met Adrian.

The Hoffmans in 2007. A four generation Barossa family of growers in the Hoffman shiraz block, L-R Gordon , Jeff , Adrian with Adrian’s son Byron : Milton © Wordley.

In 2004 we decided to start a winemaking project together and by vintage 2006 we were ready to release our first wine.

Grenache ?

Grenache is going through a huge resurgence here in Australia.

The only problem that Grenache has in Australia is that we have a woefully limited array of clones.

Our clones are barely scratching the surface compared to the actual depth that exists.

Adrian Hoffman and I have been quietly working to see if we can get some of the extraordinary Aragon clones back into Australia, we’re also now encountering a little bit of resistance on the part of the Spanish.

Due to my extensive work over the years in Campo de Borja I’m invited to Spanish clonal evaluation tastings.

The Spanish do it a bit differently to the way we do it here.

The Spanish don’t worry about the pilot winemaking thing and they quite rightly think that the winemaking is actually posting an unnecessary complication.

You did grape evaluation tastings where you actually have all the grapes with their code numbers and you actually have to fill out a grape tasting sheet.

In addition to flavour, you also have to evaluate skin thickness, colour, bunch architecture, berry size, seed colour and juice colour.

Old Bush Vine Grenache, in Adrian Hoffmann’s Sturt Rd vineyard, Ebenezer, Barossa Valley : Photo © Milton Wordley.

I’m pretty damned impressed and delighted that they actually asked me to be involved.

The first time I did it, the array of Grenache clones was astonishing and thoughts kept going through my head about how certain of those clones would impact if grown in the Barossa.

How it could probably change the whole landscape of our understanding of Grenache.

Adrian Hoffman : Photo © Dragan Radocaj.

Luckily Adrian took on the custodianship of Hoffmann family vineyards and I have access to some outstanding fruit.

This is where Adrian is just an amazing grower, every now and then he’ll say, this is a great year for Grenache, we’re making some Grenache.

This is a great year for Mataro, we’re making some Mataro.

And then there are years where he says, “no, this year we won’t worry about it.”

The whole reason Grenache was planted here was for making Port, so things like colour and tannin were never really necessary.

So we’re on a bit of a back-foot when we actually start to think about crafting it into dry red.

The first dry country Grenache we made at Rockford was in 1989, they all thought we were mad.

If you want Grenache with perfume, florals, lift, and also with an excellent acidic structure, go for Grenache on sand – I see the same thing in Spain.

It must be something to do with the water status of the vine, the drainage of the soil and the way that it has an impact on the physiology of the vine.

It’s not just specific to one region, it’s a worldwide relationship that occurs.

Don’t get me started on Mataro…. We’ve got amazing Mataro here.

The best Mataro I see here is on the same footing is the best Mataro I see in Jumilla.

Whoever was choosing that vine material really, really nailed it, it’s fascinating.

Anything else you’d like to say ?

I think the younger generation in the Barossa are making some great wine.

I’m proud to say, a lot of them cut their teeth working with me in the cellar at Rockford.

They are now able to actually decide that they want to make this style; they’re not under scrutiny or criticism and they’re creating really exciting styles again.

I mean people like Damian Tscharke.

Damian used to deliver grapes to Rockford, I remember him when he was the cheesy school kid and when he first started experimenting in one of the back sheds at his folks place, over the road from the restaurant Appellation… and to see how that’s gone from there to what he’s developed… bloody amazing.

Others like Christian Canute It makes me feel a bit old and decrepit though, having known these people when they were cheesy little kids.

This has never been a more exciting time to be an avid wine drinker because you’ve just got a choice of such fucking amazing stuff.

I think, the most exciting thing is the developments now that are occurring with white wine…like breaking away from Riesling that has to be light and fruity.

Abel Gibson walks through the vines of his Flaxman Valley vineyard : Photo © Lean Timms

Abel Gibson who also worked for me in the Rockford cellar, is now just up over the road here at Ruggabellus and his white wines are by far his best wines.

He’s really developed his own clear understandings of the style and his white wines are astonishing : it’s long maceration on the skins and he thinks carefully about the varietal combinations.

ENDS.

Production, interview & photography : Milton Wordley

Transcript : Libbi Curnow

Edit : Anne-Marie Shin

Website guru : Simon Perrin DUOGRAFIK