I first met Bhatia at our friends Kaaren and Kevin…

Alison Jane Hodder : De Vinosalvo wines, Tuscany

I often find the people who make wine as interesting as the wine they make, it’s one of the reasons I started this web site.

Every now and again you come across a really interesting and inspiring story.

One such story is Alison Jane Hodder’s journey in the world of wine.

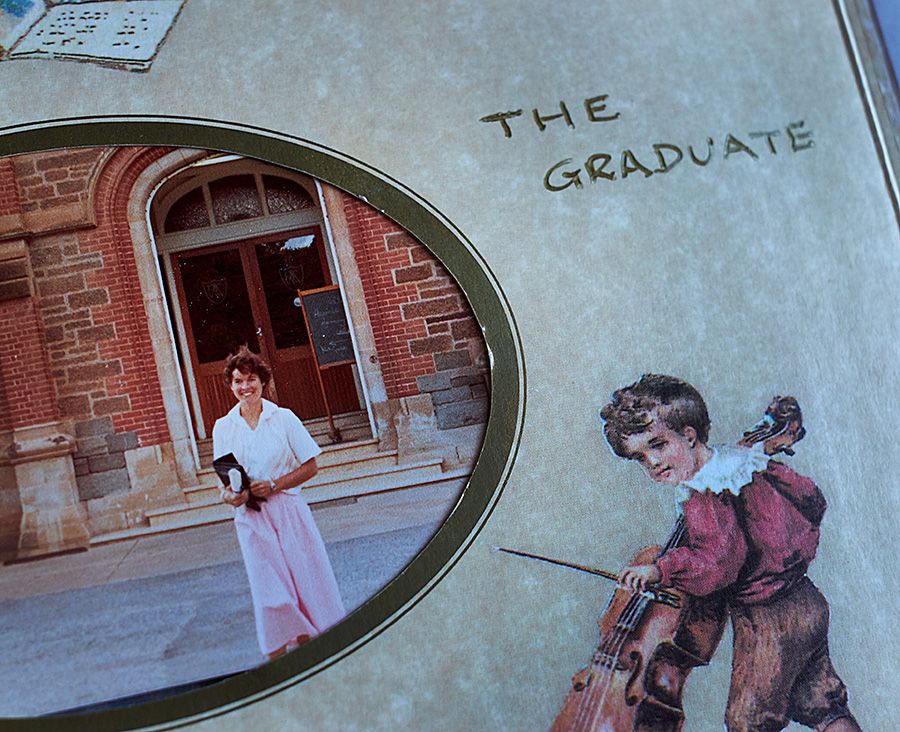

Alison was one of the first women to graduate in Oenology at Roseworthy back in 1980.

She worked in the Australian wine industry for a short time and then went to Italy to study winemaking at the University of Turin. Thirty years later she is still living in Rome.

Alison recently retired from her role as a United Nations Senior Officer in Horticulture. She is going back into her first passion wine. She and her husband Claudio have planted two vineyards in Tuscany and are making their own wine.

Shiraz in Tuscany….

It’s a fascinating story >

You were one of the first women to graduate from Roseworthy. What was that like ?

I think I was the third woman to graduate from winemaking at Roseworthy.

It was still very much a male dominated campus and a male dominated industry at that time.

There are a lot more women in the industry now but it is clear that its still not regarded by many women as an interesting career.

I was at Roseworthy from 1978 – 80.

Pam Dunsford had been through about ten years prior to that – she was the real pioneer and I think it was tough for her.

A decade on, as female students going through Roseworthy we didn’t really have too many complaints… once we’d got through the traditional orientation pranks that seemed like going back in time with the Famous Five.

There were three women in my course and there would have been a dozen others across all the different courses at the college.

Still a high male-to-female ratio but attitudes were changing and, on the brighter side, the few females were never short of admirers…

It was an interesting community of young people … a lot of them were sons of prominent winemakers all over the country, we lived together, virtually, and partied together and it was like a close-knit family because Roseworthy was a bit remote.

We did have a lot of fun and we were all so passionate about wine – that was the glue. Nobody would have taken that course if they weren’t passionate about wine.

What encouraged you to go to Roseworthy .. were your family in the wine business ?

No they weren’t…. two generations of my family had been in mining although the forebears of both my parents had been early settlers in the Barossa region.

I was born in Broken Hill and grew up there so it was just my parent’s interest in wine that I absorbed pretty early on.

Broken Hill was a wonderfully blended community, socially and culturally.

Interestingly enough there was quite a good wine and food scene even back in the sixties and seventies, partly I think because there were a lot of European migrants in the community who showed us the way.

So I combined an interest in science with that interest in wine and at 16 it already seemed like that was what I would do, no doubts.

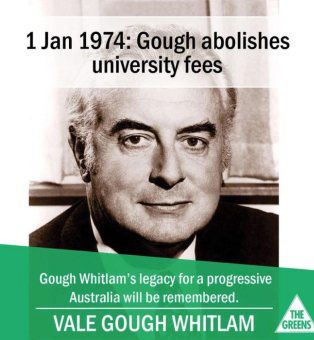

Roseworthy was most obvious pathway to become a winemaker, though Gough Whitlam’s enlightened approach to free tertiary education did enable me to fashion my own two-year liberal arts and science primer at Adelaide Uni before going on to enrol in the oenology degree course.

When you graduated what sort of things did you do in the wine business and how do you think it has changed for women ?….. There seem to be a lot more women involved now.

Well interestingly getting a job as a graduate was the real challenge for a woman at the time.

Back then people could say “I’m not going to employ you because you’re a woman”. That would be illegal now but it happened to me.

The Roseworthy oenology faculty was very well networked and they really did whatever they could to line up jobs for all the graduating students.

Bryce Rankine was the Dean when I went through and old Bob Baker was the senior lecturer who knew everything and everyone in the industry.

I had performed fairly well as a student so with a good word in from Bob, I got an interview with Seppelts.

The interview was over sandwiches during judges’ break at the Adelaide wine show.

As soon it started I realised that he wasn’t that keen on the whole idea. After a while he said, ’Well you might know your stuff but I bet you couldn’t lift a 40 pound bag of filter earth could you ? ”

I answered “You’ve probably got somebody else who’d be better suited to the heavy lifting – that’s not what I have been thinking about for the last 3 years…”. Anyway the interview ended quickly – after about two sandwiches – and obviously the outcome was me not getting a job at Seppelts.

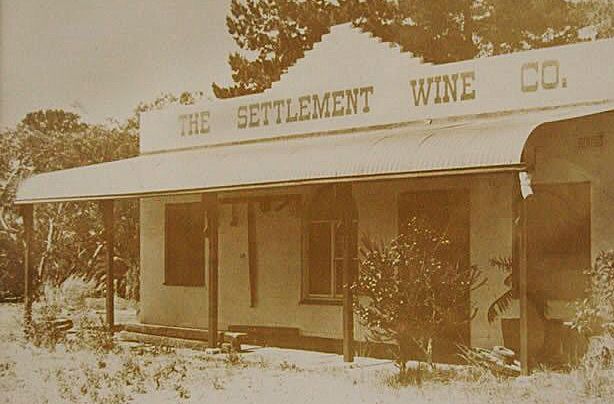

That was probably the best break I ever had because the next trick that Bob had up his sleeve was to introduce me to Vincenzo “ Enzo” Berlingieri of the Settlement Wine Co, who was also looking for an assistant winemaker for his outfit down at McLaren Vale.

He didn’t care that I was a woman and he took me on basically sight unseen…Bob’s word was good enough …the interview was just a pleasant formality and it went from there. That was straight out of Roseworthy – the day I finished exams I was on the job.

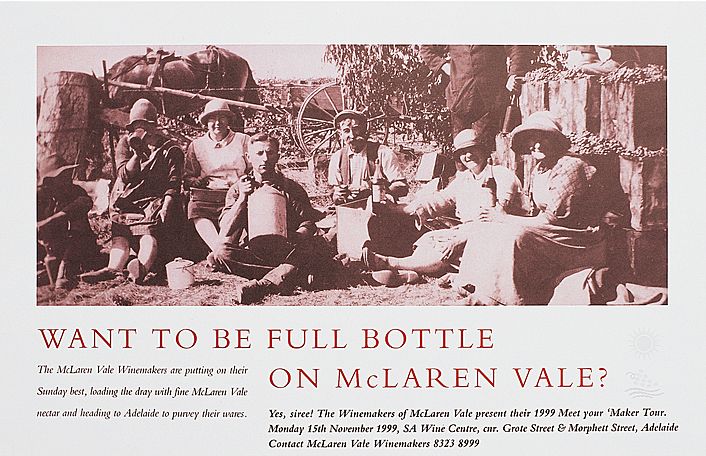

It was a fun time for me because I was just learning so much, meeting the local characters and thought leaders who have since become legends in the industry.

It was very much hands-on at Settlement and a special thing about the wine scene in McLaren Vale at the time was there was a lot of sharing; sharing know-how and sharing equipment.

Enzo would send me up the road to Greg Trott to get this and to Pam Dunsford to ask that, it was just how it was. With the young guns down at the Vale it probably still is to a certain extent …. but it is rather different from how things work where we are now in Italy.

Enzo was just brilliant as a mentor and a boss, and much of what I do now was shaped by working with him.

Like remembering always that you’re working as a scientist.

Typically he’d say “It looks like you are working as a f**k*n cellar hand but you are working as a scientist and you’ve got to work smart because we don’t have the money to invest in equipment that enables you to work less f**k*n smart.”

Having a laboratory and knowing how to analyse wine was key: if you could track what was going on in the juice or the wine, you could interpret that and adjust factors, be it picking time, fermentation temperature, time on skins or on fine lees or whatever.

You’d have the best chance of getting the result you wanted from a biological process that is very tricky to govern.

When I started working, if you wanted to have laboratory analysis in real time, you had to do it yourself… that took up quite a bit of the winemakers’ time in a small operation, whereas now I still work to exactly the same principles but I can send off samples to a very efficient lab and have the results the same evening.

I also learned from Enzo how to use what you could get hold of… you remember how it was at Settlement, using big old wood …and that started me thinking.

People were starting then to use small wood – new oak, French oak and so on – but the Italian way was big old wood. I’ve never really left that.

Italy has gone through a whole cycle of small new wood and now they are back to 5000 litre casks…

And I should mention that Claudio Berlingieri, my husband, is Enzo’s brother – that was a big part of the lucky break…

Alison with husband Claudio with a portrait of Vincenzo “ Enzo” Berlingieri in the background : Photo © Milton Wordley.

But I got sidetracked.. we were talking about women in the wine business and yes it’s great to have seen more women coming on board and emerging as leaders.

The 2015 Women of Wine awards presentation in McLaren Vale, Irina Santiago-Brown with Briony Hoare, and Rose Kentish : Photo © Milton Wordley.

Inclusiveness in any field of business tends to bring rewards to the enlightened.

It’s hard to predict that being a winemaker in vintage will ever become fully family-compatible.

Just because of the way you work around the clock for those 4 weeks of vintage – but employers and wine-growing communities in general could probably be more aware, and do more to help knit the safety nets that young mothers need.

The idea that a winemaker could dip out and run the kids to school or take a day off with a sick child when the shiraz is coming in…

I’ve never had to deal with that but I can totally sympathise with anyone who does.

What took you to Italy ?

It was mostly me thinking about how to get an edge in the wine industry in those early years…. being a woman in a male-dominated industry.

I started to think that I needed to get a post graduate qualification.

At the time if you went for a post-grad in winemaking or in viticulture you went to Davis in California, Geisenheim in Germany, Montpellier or Bordeaux in France, or Turin in Italy.

I chose Turin over the others because I was pretty crazy about things Italian, and not least because I was offered a bursary by the University of Turin.

The view from Alison and Claudio’s balcony in the hillside village of Cinigiano : Photo © Milton Wordley.

The idea of being in the centre of ‘Barolo-land’ just tipped it for me.

I didn’t speak Italian when I left for Italy in 1982 and did a one month crash course when I got there which set me up pretty well.

I spoke French fluently so it was easy enough to switch over to Italian .

That was a post-grad specialisation course in viticulture and oenology at the University of Turin and I did a vintage at a winery in Canelli while I was there.

I was only planning to stay in Italy a couple of years and head back to Australia – then in the middle of all that a different kind of job came up.

I was a broke student so almost any job would have been interesting but this job was something else… it was as a consultant at the food and agriculture agency of the United Nations – headquartered in Rome and I was twenty-five !

Opening of the second International conference on Nutrition in 2014 at UN headquarters in Rome in 2014.

It was just a short gig initially but there I had another good mentor and soon it turned into a proper job which has now lasted and grown with me for more than thirty years.

I retired from that position in April this year. My title was Senior Officer, Horticulture.

I ran the horticulture program which in the last ten or so years has built a strong focus on sustainable horticultural development. Our bosses and our clients are basically the governments of the UN’s 193 member states.

The agency I work for does all sorts of different things – standard setting: from setting maximum pesticide residue levels and safety standards for food to international quarantine standards, technical assistance and policy guidance.

Much like a great big department of agriculture with a world-wide mandate.

Much of my work was in tropical countries, focused on fruit and veg, up until the early 90s, then following the break-up of the Soviet Union I also worked with a number of former Soviet and east european countries as they were transitioning towards market economies, from State farms to smallholder based agriculture.

Viticulture was a significant part of that and I’ve had amazing opportunities to work with governments on developing their viticulture industry support strategies.

I’ve done that in Albania, Georgia and Armenia and I also did similar work at an interesting time in Malta before it joined the EU.

Sustainability in viticulture is a huge international issue – are there some countries doing sustainable viticulture better than others ?

I think the countries that are doing it best are those that are not over-legislating for it.

Those pushing for sustainability pathways rather than sustainability barriers. Most of the major wine-producing countries are now pushing pretty hard on the environmental side in viticulture.

In the EU they use incentives a lot, producers can actually get subsidies – sometimes it’s tax breaks but usually it is actual money to encourage producers to adopt more sustainable practices.

In Europe there is sort of an accepted equivalence between organic and sustainable – so the subsidies for sustainable viticulture are increasingly being channeled to certified organic producers. I tend to see sustainability as a pathway rather than a measure of absolute values. I mean if each grower and each wine region can steadily make sustainability gains year by year against their own performance record – that’s more useful in the long run than being able to say “vigneron Jacques is more sustainable than vigneron Bruce”.

Dr Irina Santiagoz-Brown and husband Dudley promote sustainable farming on their winery Inkwell in Mclaren Vale. Photo © Milton Wordley.

It should be more about getting growers to embrace sustainability as something that’s good for them, rather than saying “you will do this or you will be fined”.

Then there are multiple facets to sustainability, where the social and economic sustainability factors need to be in balance with the environmental factors. There’s no point in being so sustainable that it puts you out of business.

From the social and fair work standpoint I think this whole women in wine discussion is a very interesting one and we certainly haven’t resolved all the issues beyond employers no longer being able to actively discriminate against hiring women.

If we look at fair work criteria more closely as one indicator of sustainability, it seems that some countries are improving while others are going backwards, with vineyard workers now being employed on worse terms and with less protection than some decades ago.

This doesn’t just apply to the wine business but if we want to claim we’re sustainable, exploiting workers shouldn’t be in the mix.

So you’ve come back to winemaking after thirty years…

Yes after thirty years of being an ‘agricrat’.

It’s something I’ve had on the backburner for all those years and it became a possibility when my husband Claudio and I started working on it together around the turn of the millennium.

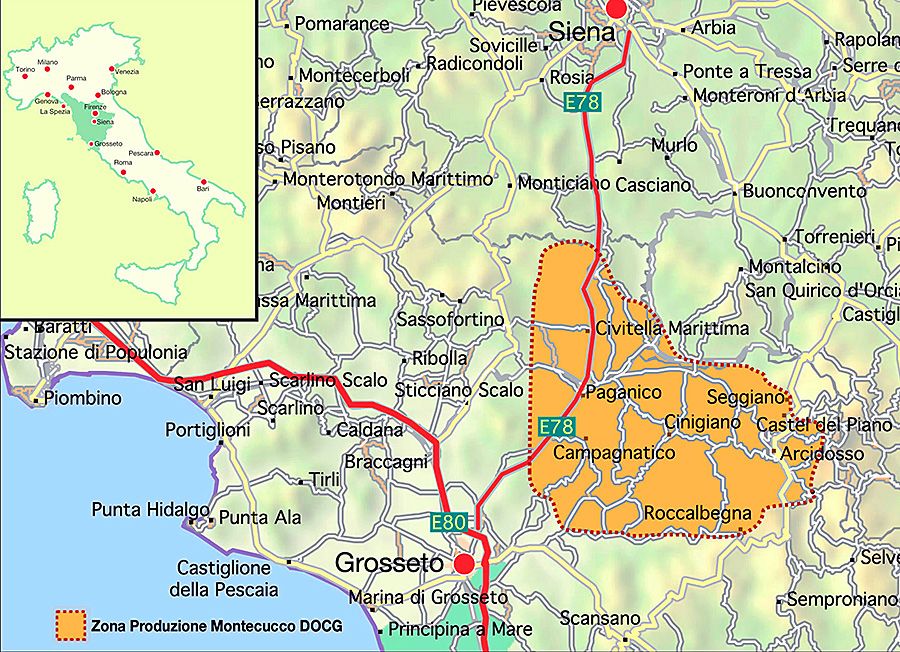

After much searching across central Italy we found our ideal vineyard sites in the Tuscan Maremma.

Claudio has handled all of the finance and the bureaucratic part of it brilliantly, which has allowed me to dedicate myself to the technical part and the actual design of the wines.

We have done three commercial vintages now and it has gone pretty well.

We surprised ourselves with our first commercial vintage… we made three wines and we took medals in the Decanter wine awards with all three of them.

We just put them in, it seemed like a good thing to do as part of the learning process, and bingo!

They are quite prestigious awards…

Yes and also objective – with wines from all around the world judged blind against uniform quality standards.

We entered a straight shiraz 2013, a sangiovese-based blend that also had a bit of shiraz in it, then a shiraz reserve that we aged for longer in old wood.

You don’t see a blend of sangiovese and shiraz often – what made you choose that ?

Sangiovese is a given in Tuscany and I love its colour, it aromatics and its quasi-saline quality.

I find the two varieties fit together very well – it was sort of a hunch because no one was doing it in Tuscany when we first planted our vineyard.

But I could just see that sangiovese tends to have a big gap on the mid-palate – that’s also what many Tuscans say – that a bit of shiraz would help to fill.

I think the reason why in Chianti they traditionally used up to six different varieties in a blend with sangiovese was partly to fill that gap on the palate… as well as boosting the colour and alcoholic strength.

What does shiraz do ?

It fills the middle palate because shiraz is naturally quite full on that section of the palate.

The respective aromas tend to sum to give more layers: whereas in sangiovese you’ve got those red fruit characters – raspberry and cherry – shiraz even as the minor partner lends more black fruit aromas – blueberry, blackberry and elderberry.

Also we get some floral and spice lift from the shiraz – like violets and pansies then something like juniper berries and pepper.

You have to be a bit careful because the weight of the shiraz can tend to drown out the more delicate sangiovese characters .

Your website attributes the character and quality of the wines to the terroir and careful vineyard management. Can you talk about how you’ve knitted that together – starting from scratch 6 years ago –

I probably wouldn’t have initially thought you would get so much variation in wine styles just from the combination of soils and microclimate – but where we are we’ve certainly discovered that you can.

We have 10 acres, half shiraz and half sangiovese plantings.

We’ve actually got two separate vineyards which is a handy thing to have in what has turned out to be a moderately hail-prone zone. If hail goes through an area it doesn’t take everything out, it just takes a strip.

So if it hits one vineyard, it doesn’t hit the other.

Those two vineyards are about ten kilometres apart – that also gives a different set of soil and microclimate combinations to work with and we’ve already seen different ripening times and wine characteristics resulting from that.

What is peculiar to where we are in the Maremma, part way up an ancient volcanic Massif called Monte Amiata, is the microclimate.

It’s not as warm as you would expect and you’ve got day-night temperature variation which for me clinches it – it makes such a difference to the aromatics you get in the ripening grapes.

Alison and cellar hand Simone install a solar panel in one of the vineyards : Photo © Milton Wordley.

Being wedged between that mountain and the sea gives rise to alternating air currents that bring the night temperatures right down.

Proximity to the (extinct)volcano, also gives us very deep clay soils which do interesting things ‘viticulturally’.

Our vines are quite vigorous and we have to restrain their zeal with repeated shoot and bunch thinning and hedging to keep the canopy open and to lighten the crop.

The main vineyard is on a hillside with a southerly aspect and that is also insurance for getting the crop ripe in that one cool year that comes by every five or so.

The vines are six years old, we planted them in 2010.

They’ve certainly got deep roots because of the depth of soil, and the clay makes for very distinctive characters in both the Sangiovese and the Shiraz – but more so in the Shiraz.

Clay soils are shunned by most growers in Tuscany, but knowing what magnificent, elegant wines clay can generate in France and in Piedmont I went for it, no regrets.

Alison’s Tuscany base is in the hillside village of Castiglioncello Bandini in Montecucco DOC area : Photo © Milton Wordley.

The sustainability part of it, Organics and the weather ?

The sustainability part of it ….you are not going to ever really taste the difference between something which is produced sustainably and something that is not… but at least I know.

I’m comfortable telling people that I am doing whatever I can to make sure the soil in our vineyards doesn’t end up in the creek at the bottom of the hill. Using permanent soil cover that is compatible with the climate, we are able to keep the soil where it is and to enhance the soil biota.

Our vines are totally rain fed, we haven’t ever put any water on since the first summer we planted them.

The rainfall is between 600 and 700 mls – it’s like a good part of the Barossa or up in the hills above McLaren Vale – where traditionally viticulture was rain fed.

So having these deep soils and a drawn out rainfall distribution pattern, we can actually get good crops without having to put any water on.

In most of Italy the rainfall distribution is generally pretty good for vegetative development and it stops the vines from going into stress. Compared with many of our winegrowing areas in Australia you get Spring rain for longer and Autumn rain earlier and a bit more rain through the growing season.

The downside is higher disease pressure – particularly fungal diseases.

We thought about going organic initially and I looked around at what other people were doing.

There is certainly a strong organic movement in Italy and a lot of people are finding a marketing edge for certified organically produced wine, in northern Europe in particular.

But we made a choice.

Copper sulphate and sulphur are the permitted disease control chemicals in organic agriculture and their use is not without environmental consequences.

When I considered the number of anti-fungal treatments you would need and the fact that you need to apply them as calendar treatments rather than weather-based…

I thought. No – for the moment it is probably better to follow integrated pest management principles, trying to keep the use of chemicals to an indispensible minimum.

We use predictive techniques and methods, for which having pretty accurate and reliable 5-day geo-referenced weather forecasting is the real breakthrough, and so far we’ve stuck to that.

The Winery.

In the winery it is again about going back to the things that I picked up in the Settlement days.

Alison in her small winery, Querciasola (lone oak) with cellar hand Simone Rabagli : Photo © Milton Wordley.

The winemaking is very, very simple, low tech, labour intensive… we use pump overs, punching down, a basket press.

We use stainless steel fermenters and the wine is aged in stainless steel until the malolactic fermentation goes through, and then partly in old wood.

At the moment I am using 500 litre puncheons as the standard, because they are relatively easy for us to handle in our space-challenged winery.

It’s French oak, generally 2nd or 3rd use.

Quite a lot of Slavonian oak is used in Italy and I’d like to use that too if only I could get hold of it in the barrel format I need right now.

American oak is almost unheard of – happily because I hate it – cant bear it .

How does the way in which you work in Italy compare with how it might have been if you’d stayed here? Do you see any similarities or differences ?

It is hard for me to really compare because in Australia it was decades ago and I was working for someone, whereas in Italy we have managed to put together our own thing.

Certainly even the small producers in Italy are quite competitive and individualistic and that sharing culture I experienced in McLaren Vale is not the norm.

That said, we have been really fortunate to have supporting vigneron friends and neighbours in Tuscany.

A really big difference is the rules; in Australia you can do whatever the hell you like… there are really no holds barred and there’s nobody breathing down your neck saying, “This is what you have to do”.

Environmentally you have to be very careful – as you do in Italy – but on the winemaking front there are really very few rules that you have to abide by and I don’t think there are such overbearing control mechanisms as there are in Italy’s guarantee of origin (DOC) systems.

For producers in Italy the DOC is really vital for marketing: we couldn’t afford not to work within the system but the moment you do you have to abide by those rules.

Italy is divided into hundreds of little territories …. we’re in one – Maremma Toscana DOC – the coastal part of southern Tuscany and another smaller one within the same territory that is called Montecucco DOC.

There are normally rules about which varieties you can grow, whether or how they can be blended and to some extent also how long the wines need to be aged, whether or not they have to be aged in wood and so on.

And then all your wines have to vetted by certifying bodies before they can be released. It would be hard to imagine having to deal with any of that in Australia.

Doing the experimenting that I have wanted to do, especially with Shiraz, hasn’t been so easy – but we are getting there. Happily our Maremma Toscana region is gaining recognition now as a new and happening DOC, and the rules are more open to using international varieties.

Favourite Wine styles …Memorable wines ?

Tasting Best’s Great Western Shiraz was a turning point for me … one of the really brilliant things about the course I did at Roseworthy was that they put students in buses and carted them all over the country.

That gave us deep exposure to what was going on in the Australian wine industry at that time – and it was pretty exciting.

Best’s for me was the highlight of one of those tours.

Viv Thomson told us about how they struggled with frost and how every fifth year they would lose their crop.

You’ve got to take your hat off to people who persevere with that… but when I tasted that shiraz – its elegance, its brightness – it was like nothing I had ever tasted before.

I had also had some exposure to northern Rhone syrahs – Côte Rotie – by then and so I thought then that cool climate shiraz was something I definitely had to explore.

I don’t claim to measure up to either of those icons but that is certainly where the inspiration comes from.

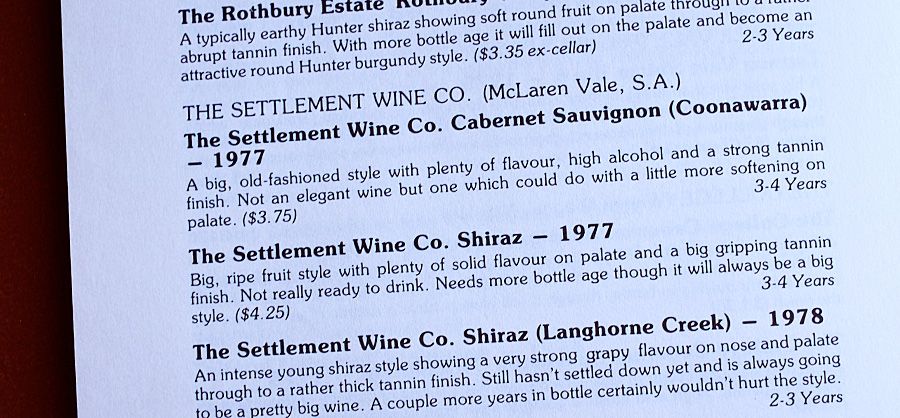

Other memorable wines – I still have a special attachment for long-ageing Settlement shiraz wines of the late ‘70s.

It was the way Enzo made his Shiraz at the time that I found so distinctive: classic big wines from ripe fruit, but their bright acidity set them apart and gave them the necessary structure for graceful ageing.

There are a lot more favourite wine styles that I would like to play around with and hopefully will in time but at the moment we are concentrating on shiraz and sangiovese.

Alison and Claudio at their ‘Dream Site’ : hopefully one day the site of their new winery and high altitude vineyard near the village of Monticello Amiata. The extent volcano ‘Monte Amiata’ can be seen in the background : Photo © Milton Wordley

If we can get hold of a patch of volcanic soil a bit further up our extinct volcano, I’ll probably make some white as well…there is a variety I like in central Italy called Malvasia Puntinata and also Fiano.

Both do very nicely in cooler areas with volcanic soils and make structured whites with body and soul.

Where did you get the idea for your brand….Your labelling is unique and has to do with history.

One of Georgian artist, Levan Mosiashvili’s paintings on the wall at the winery : Photo © Milton Wordley.

The name de Vinosalvo is from the story of Galfridus who is our hero in many ways.

Galfridus was a medieval English scholar, a real polymath…he wrote works of poetry and also a treatise on making and conserving wine “De vino et vitibus conservandis.”

He actually put this together by researching the works of the classic Roman period – of Cato the Elder and Pliny – that would probably otherwise been lost to the dark ages… so he got the nickname de Vinosalvo which means the “saviour of wine”.

Galfridus de Vinosalvo was actually active as a writer and a scholar in France and also in Italy – so the idea that a ‘Pommy’ could have had such a pivotal role in the evolution of wine science appealed to us.

So Galfridus was a natural choice of name for our top shiraz.

The labels are from paintings that we own, painted by a Georgian artist, Levan Mosiashvili, who is a friend of ours. He has given us the permission to use the images on our labels.

In some cases we started from the picture and came up with the name… in other cases we did it the other way around.

In Santàrio, the name we made up for our first shiraz, with one stroke of the pen we beatified a heretic and made a dear old bloke called Ario very happy.

The blue man on the Santàrio label is wearing the traditional tunic of the Georgian winemaker. Many of Levan’s painted images from this phase are agrarian scenes – he is also an agricultural science graduate and knows rural Georgia intimately..

When it came to this one we actually had the painting of the chooks and thought that would be a nice label but wondered what to call it – .. what would give meaning to three chooks …

Claudio said, we could cast back to ancient roman times and the practice of augury – the interpreting of omens by studying the flight of birds and the entrails of animals and so on.

There was one particular form of augury generally used by the military – called auspicium ex tripudiis – in which auspices for impending battles were read by interpreting the feeding patterns of fowls.

So we had found a name for that wine – Auspicium. We may have painted ourselves into a corner with these names because while your average educated Italian could pronounce them and at a pinch could spell them and therefore google them – nobody else probably can but we will see how it goes….

Levitas – the name of our sangiovese just means levity, lightness, so that was a giveaway for a painting depicting a party.

Anything else you’d like to say ?

Embarking on the next phase of my life as a retiree will coincide nicely with the need to dedicate much more of my time to growing our business.

But I expect I’ll also have time to do some committee work, perhaps also some judging and tasting on panels, and I look forward to that. I’d also like to have a crack at introducing winemakers’ social dinners – something I remember from those McLaren Vale days – as a way of bringing local winemakers together in an informal setting.

Over a steak once every few months we used to taste each other’s wines, swap ideas but also insults, and generally have a good yarn and a belly-ache about problems we were all facing.

I’m sure it helped to keep the producers united and nurtured that collegial spirit.

Our local friends say it couldn’t work in our district, which has of course made it into a perfect challenge for me….

A tasting of De Vinosalvo wines at Parade Cellars, where you can buy the wine in Australia : Photo © Milton Wordley.

ENDS.

Production, interview & photography : Milton Wordley

Transcript & edit : Anne Marie Shin

Website guru : Simon Perrin DUOGRAFIK