The first Q&A for the year is one of the…

Peter John : A.P. JOHN Coopers, Barossa Valley

If you have ever had a tour of Penfolds Magill Estate Cellars, you would have noticed Grange and St Henri are matured in different sized barrels.

In Champagne earlier this year I noticed at Lanson the amount of wood they used to mature the Champagne.

I was not so aware of Champagne being aged in wood.

The use of wood to mature wine has interested me for years.

AP John is Australia’s oldest cooperage, they recently celebrated their 125th anniversary.

The celebration night is still talked about by those that were lucky enough to be there.

Peter John, the AP John Managing Director and Master Cooper, is the fourth generation John to run the family owned business.

It’s a fascinating yarn.

Here’s his story

What is the history of ageing wine in wood.

A damn side longer than you and I might think, quite simply – anecdotally there is historical evidence to suggest that barrels were used in wine in some form over 2000 years ago.

Certainly not in the refined aspect that they are today and you’ve got to remember that.

A Row Of Amphora Wine Vessels From The Ruins Of Pompeii : Photo vinepair.com

The barrel is essentially a container for all manner of goods, dry goods, grains, beers it was all known as slack cooperage.

I think somewhere along the way people discovered it was pretty damn good for containing wine spirits and the like, but clearly if you go back to the start, clay amphora were probably more prevalent than barrels as it was just easier to shape and use than taking pieces of wood and bending and twisting them to make an impervious container.

In terms of the wine or the spirits industry there is quite a bit of evidence from the late 1700’s and early 1800s forward, that people really started discovering the benefits of ageing in wood. They noticed that rather than just containing, the wood was also having a maturation effect. The oxygenative material of the barrel, the vascular nature of the oak or the wood they were using was beneficial to the ageing of the wine.

‘AP Johns’ have just celebrated 125 years, quite an achievement.

We celebrated the 125 last year, one year late – as often happens, we just didn’t get time.

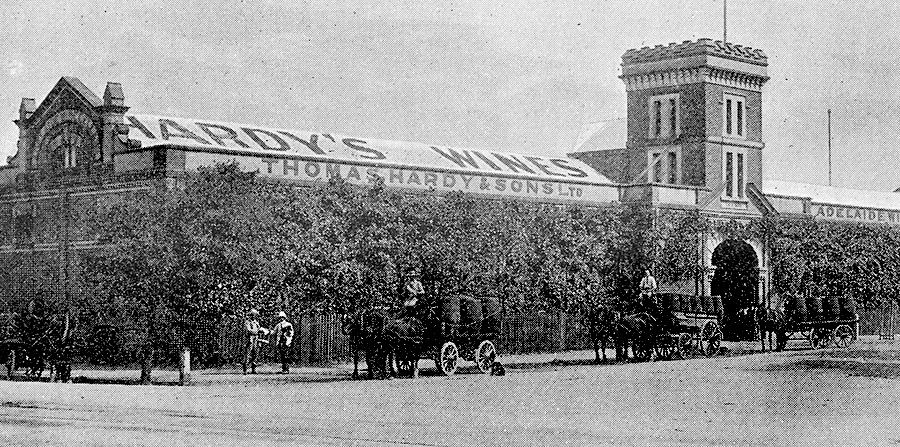

A brief history. CP John, Christian Paul, my great grandfather served his apprenticeship from 1889 onwards, then worked as the resident cooper at what is now the Chateau Tanunda.

Records show that from about 1895 he started employing apprentice coopers. I’ve still got his old wage books, written diagrams and formulae for barrels from that time – it’s just great history.

He worked a small cooperage at the back of Chateau Tanunda until around 1912. He apprenticed his son AP in the late 1890s, AP worked with CP at the Chateau, then when CP passed away at a fairly young age In 1913, AP was left to look after his mother and raise all his nine siblings.

CP was only in his early thirties – amazingly tenacious people these old Barossa Deutschers, incredibly hardworking and god-fearing.

AP took the reins and moved the cooperage to its present site on Basedow road. In 1925 he built a new bespoke cooperage, and the business grew rapidly, at one stage he employed nearly 60 people. It was then called ‘AP John and sons’.

He had 10 children, in the German way, all the five boys joined the business and all the girls stayed at home looking after mum. By the time the great depression hit AP was churning out about 110 barrels per day.

These barrels were ostensibly called ‘one trippers’ for shipping wine back to the Empire. All those barrels came back with wine in them and they often did a few trips and went back to the cellars and stayed here for many, many years thereafter.

That whole era was based around mostly fortified wines – some dry varietals and some wines that were made as dry wines that were triaged afterwards and turned into bubbles and all that sort of stuff as well.

Dad took ownership of the business in 1960, Mum and Dad were sole proprietors of the business – Dad was the fifth son of AP.

It was an era that was very difficult for cooperages all around Australia because until that stage, all transport of wine was done in the barrel – so it was a storage vessel as much as a maturation vessel.

The advent of stainless steel knocked the cooperage business for six for quite a while – but at the same time the development of the dry varietal side of the industry was commencing.

I came along into the business in 1976.

Life is all about timing – and I timed it pretty well. It was coming off the bones of its backside and lots of exciting things were starting to happen in the Australian wine industry.

Fortifieds diminished and great table varietals were coming along.

Obviously there were some amazing wines that were made in the 50s, 60s and early 70s , but the recognition of the fact that a small wood oak barrel was integral to the maturation of wines meant that my timing in 1976 was perfect.

The ‘AP John and sons’ business could only go up and it went up tremendously.

Ever think of doing anything else ?

Every day I think about yabbying, going fishing or driving a motor car very fast around a racing circuit – but have I ever thought about doing another vocation – not at all – not since I started coopering.

A lot of my cousins went in to the wine making side of things.

The rest of my family were viticulturists – so we are all inextricably linked to the industry anyway. The very dirty and tough life of a cooper as opposed to a wine maker ?

I was good mates with my two nearest cousins Philip and Stephen John.

Both Philip and Stephen went through the era when they could learn on the job here in the Barossa.

Seppelts and Gramps were great businesses to take in secondary school leavers who wanted to be winemakers. They put them to work as winemakers from the ‘get go’, learning from the bottom up in the cellar – providing all the hands on training they could – whilst they did after hours schooling at Roseworthy.

Philip went on to be one of the movers and shakers in Lindemans.

Stephen went to work alongside Wolf Blass and Chris Hatcher, and then went out on his own.

Their job always appeared very glamorous to me and for a while I thought about winemaking – but I think I got to year eleven and I decided that I wasn’t going to go to university and I didn’t want to be a winemaker.

I had been working part time at the cooperage since I was a kid and I really wanted to do this thing.

The day I asked Dad for an apprenticeship, he kind of looked at me sideways. I’m sure he thought where did that come from.

I did my full trade – I learned everything on the job.

I was still living at home with mum and dad, it was a tough transition because our relationship as a father and son changed.

We were very, very close, had a lot of fun together fishing, yabbying, shooting , sport all that sort of stuff together.

It was an integral part of Barossa life back then – the subsistence lifestyle of the old Barossa Germans where they had their old orchards and vegetable gardens and they hunted game , wild hare, rabbit, duck there was even wild pheasant and quail on the Gomersal plains.

It was a boys own adventure and that’s what I did as a kid with my dad.

Once we started working together it was very difficult. We still had a great relationship but the boy and the Dad thing changed.

I was very fortunate because I had a dad who was very, very empathetic with where I wanted to go and what I wanted to do with the business – he gave me free rein.

I thoroughly enjoyed rebuilding the business with Dad. Then he got to the stage where he said ” OK boy off you go – it’s getting too hard for me, too complicated.” I was 26..

How has the business changed ?

In my time, lots, especially technically. We have had to design and create new machinery and introduce new technologies into the workplace which were more appropriate with the way society was going not just the wine or cooperage industry.

Kids were coming out by the early nineties with computer literacies which meant they didn’t want to work for twenty years to develop those incredibly difficult hand-skills we needed.

We were the first cooperage in the world in 1996 to introduce computer numerical control machinery that hadn’t existed in the cooperage industry before.

We got a lot of our machinery from Germany.

I actually went to a general woodworking expo in Melbourne in the mid 90s, took Dad along and saw some stuff – and said ” Fuck !” we could use this sort of gear. Dad said, “Its just not available for our industry.”

So I hopped on a plane and went to a little place called Schopflock in the Schwarzwald south of Stuttgart, in the Black Forest.

I fronted up to them and said, “Well this is what we do, we make oak barrels and we want to have some pre fabrication machinery that will do these applications.

Can you do it ?” they kind’a said yeah.

It was a two year program of developing one machine that still sits in the cooperage to this day. It was very exciting but the industry was growing so rapidly it was a no brainer to spend money on this research.

Then there was this chance meeting (which often defines peoples lives) with this bizarre gentleman, a lovely chap called Arthur Firminger. Arthur had been working in Adelaide creating unique machines for the motor industry.

He was making testing machines such as those to test shock absorbers, for Monroe Wylie when they still existed.

He developed this amazing CNC machine for this industry. You might think what the fuck has this got to do with a cooperage – but bear with me, he put a whole range of these machines into Monroe’s plants right through the US.

I had a chance meeting with this guy and said “I’m thinking of designing this machine to do this,this, this and that – it involved encoders and survey drives and all the stuff he was using in his industry.

He said, “I can build that”. I thought, “I’ve heard that before…. how much is that going to cost… show me the designs…” and it went from there.

We had a great relationship for about 12 years where he designed 6 or 8 machines for the cooperage – bespoke unique machines. They were expensive because they were one – off’s – but they worked and they are still in our cooperage today. A lot of people came in, looked and said I’d like to design a copy of that . That was right through the late 90’s – early 2000’s not that long ago, back when the cooperage industry in Australia was peaking.

We have also seen oak chips introduced.

Oak alternatives were developed in the new world both here in Australia and in California as a method of introducing a flavour medium to bargain basement booze.

When you are looking at D grade fruit that doesn’t even show any varietal expression, intelligent use of oak alternatives can add a dimension to that wine very economically.

Oak alternatives started their development in the late 80s, very crude and very different to what we do today.

Have a look at Lindeman’s ‘Bin 65’ charddy, one of the first great success export stories, incidentally a wine totally developed by my cousin Philip John, it was his baby.

You could argue that it was the worst thing that Australia could have done as a wine producer but it helped get the Australian wine business off the bones of its arse .

In the late 80s there were great things happening in the wine industry but were sales great ?… was it going ahead ? …No. Once again necessity is the mother of invention. Oak alternatives are a very necessary part of the wine industry in Australia, California and also in the old world.

You wouldn’t believe it but there is a shit load of oak alternatives used across Italy France and Spain as well.

AP John export barrels, where to ?

Currently we export to New Zealand, South Africa, Spain, California, plus a little bit to China – that is just starting.

We are very proud of that export market – it’s a minor share of what we do – in a good year we will top out at about 20% but its very important to us because it fills out those quiet winter months where the southern hemisphere just isn’t looking for barrels.

Our first export foray was into South Africa in the late nineties.

Luckily people were searching out our product on the back of what we were doing with certain wines and certain producers here in Australia.

It was the biggest mistake we ever made because we weren’t objective about it, we were led by the customer.

They believed they wanted something that really wasn’t any good for them and we didn’t know.

Quite frankly it was a dismal bloody failure for the first couple of years. – we kind of walked away, stepped back and said hang on – the cultivars, the regions, the style of wines are so different, so we have to become a little bit more clever about what we are doing.

How did you go about becoming more clever ?

Learn more ! I think we’ve got to understand that to be a really good cooper you’ve got to understand just as much about the vinification process as the winemaker does themselves.

You need to understand the region in which you might be supplying oak, you need to understand that region’s idiosyncrasies and unique characters according to a given cultivar or grape variety. Then you have to say “how can our oak work best with what these guys or girls are doing with their wine”.

That all takes a long, long time and it would be fair to say that from the late eighties through until today it’s been this gradual process. – but with huge momentum.

If you look at where we are today, the Barossa has always been our core and will always be our base.

The Barossa has a particularly distinctive style within the wines it makes but to say that the Barossa just makes one style of wine is very simplistic.

So if we look from Eden Valley across to north western Barossa to western Barossa – southern Barossa – everyone is trying something different and we need a barrel to work with all those people.

Then we have to ask how are we going to be relevant to people sitting at the bottom end of the Mornington Peninsula or somebody at Coal River in Tassie.

Our current ambition is to become viable in New Zealand and to do that we need to learn a lot more again because the wine styles through Martinborough, Marlborough, Central Otago are wildly varied- everyone is looking for something different.

I would never say we can be something to everyone in the market place but as a mission I have said to the guys “I don’t want to put a hard timeline on this but over the next 5 – 10 years I want us to have a position in those markets and be recognised as an oak supplier who is totally relevant to what those guys are doing.”

We had taken that approach in every region in Australia from Margaret River through to the Granite belt in QLD and every little spot in between. So we service every region and by and large we have products that are relevant to what people are doing. Is that difficult ? …Absolutely !

Two of Australia’s most well known wines Penfolds Grange and St Henri are aged in quite different barrels. What’s the background ?

Well, Grange is matured in small wood – hogsheads of 300ltrs. StHenri harks back to the very traditional Australian big wood size of 500 gall / 2500ltrs for its maturation vessel.

Penfolds chief wine maker Peter Gago in the St Henri cellar at Magill Estate : Photo Penfolds © Colin Page.

In terms of the American oak that we supply for Grange – its a very specific barrel, proprietary to the relationship we have with Penfolds. Typically the American oak that is used on Grange now is so different to ten, even twenty years ago – low cis – oak lactones – low coconut.

It’s very supportive oak …it’s nearly a structure barrel now where it stands fruit up and stands it proud – gives it length and line.

I taste with winemakers who have looked at those wines in barrel and kind of said “what the fuck have you done to your American oak ? ” – like it was just this watershed thing that happened overnight and you’d say – well this has been a long time coming – it didn’t happen overnight.

Quite a few people have said ” That is so French like – so un-American “ You’ve got to bear in mind that every year great wineries like Penfolds go through a critical selection process to manage the seasonal variations so that they have parcels of fruit that are going to marry with the recipe that we have put together and evolved over 50 odd years.

The winemaker is central to that because if you don’t understand the variances in the oak selection, the nuances of that marriage will be lost.

With St Henri, as it is matured in large vats, the cooperage techniques for big wood are different again.

You could take exactly the same oak selection, mill it totally differently, season it the same, try and cooper it the same, and you would get a different characteristic coming out purely by dimension surface area , surface area rates , extraction rates across that surface area of that larger vat.

What is the difference ?

For starters, the vascular nature of old growth, very fine grained American oak is similar to that of French Oak. You need to consider the ability for the wine to enter and exit the oak interface with very fine grained wood.

Oak trees in the Tronçais forest, Allier, France. The largest oak forest in Europe. Photo : CEPHAS © Mick Rock

You have a much higher percentage of spring wood – which is also very vascular ; open pores mean higher oxygen level at the oak interface itself – so maturation rates are going to be very different to those which are in a very, very broad grained barrel.

Broad grained wood has a higher percentage of summer wood – harder, denser, less pervious – so that one little factor is going to influence the maturation and the extraction of flavours.

Then of course – you have the structure of the annual rings themselves – holding different flavours according to the structure of the wood.

You start breaking all that down as science and you are getting enormous effect and difference just in grain structure alone even with the same species of wood, trees grown along side each other .

That was a lot of what we did through the late 90s.

We were just trying to debunk the myths behind generalised nomenclature such as fine grained, medium fine grained, very fine grained …that was associated with oak selection.

Wood and white wine ?

Let’s start with Champagne.

The renaissance of big wood as we ‘coopers’ would call it in champagne is quite amazing. I don’t think the Champenoise like to broadcast the news but in fact you would arguably find some of the earliest evidence of big wood usage in Champagne.

In the last 10 – 15 years in particular, there’s been a hell of a replacement program of that big wood – its anything from 25 hectolitre tanks upwards.

A lot of the base wines such as chardonnays are vinified or matured in oak right from the ‘get go’.

Many people in the wine industry are aware of this and that oak influence has trickled over to here in Australia as well, particularly for dry varietal still white wines.

Big wood usage for premium Aussie Chardonnay has been on the rise for a decade or so – not always vats, but most particularly puncheons ( 500ltr ) or Demi Muids ( 600ltr ).

Predominantly those sizes in French Oak but occasionally some in American Oak.

The 125th Celebration, a journey through the cooperage, was a night many will remember …

Peter and Catherine at the 125th Celebrations : Photo © John Krüger

It wasn’t so much an exultation of the Johns being in Australian coopering for 125 or so years.

It was really a celebration and a journey of the whole of the Australian wine industry.

We both feed and feed from that community so its just a wonderful symbiosis.

When Cath and I were wondering what to do for the 125th, we agreed that the last thing we wanted to do was to have a boring sit down dinner for 200 people.

We wanted this great celebration to look at where we came from, where we went, what we became and where we are going.

So we planned a physical journey through the cooperage highlighting eras of the Australian wine industry.

All along the journey we looked at some great Australian wines, starting with amazing old fortified wines.

Fiona Donald and Warren Randall from Seppeltsfield came aboard and put special blends of old fortifieds together for that.

We set up stations through the cooperage so we could highlight an era according to production process or whatever it might have been and of course we looked at wines from those iconic kind of benchmark turning points in the wine industry.

A few of the 125th Wines : Henschke 1978 Mt Edlestone, Penfolds 1990 Bin 90A, Seppelstfield museum Oloroso blend, and a Saltram 1966 Bin 2 Burgundy : Photo © John Krüger

I think that just kind of struck a chord with everyone. The guests that night were fantastic – you can turn great food and booze on and it won’t work if the people aren’t with you. I think Mark MacNamara, who we engaged to create the food and run the night, was scared shitless when I threw the concept at him. He just didn’t get it for some time but then everything just seemed to work.

Stephen Henschke has a look at the Henschke and Saltram wines at their table during the 125th Celebrations : Photo © John Krüger

We planned that show for a year – I think we spent more than a thousand bucks for every year we’ve been in existence on the show – but that wasn’t the issue. It was just a fun, fantastic night with great support from the industry in doing it.

You two sons are now involved , how do you see the future ?

Peter with Alexander and William in the cooperage : Photo © Keturah de Klerk

Yes, Alex and Will ; both two of the best young men you could wish to know.

Alex just turned 28. Cath and I took that European approach and pushed them right away from the business.

We said, “Go and do something else – get another vocation, do something else before you think of coming back here.”

Alex went off to Uni and did civil and structural engineering, a double degree with finance. He hated it with a passion, he bumbled through and then finally said to me ” You know what I have always wanted to do – come and work with you to create this next generation.”

In 2011 he came on the payroll with us – we put him straight into a ten year structured, modularised training program where he had to learn his trade but then he had to learn every other aspect of the business.

Interestingly like me, Alex had harboured desires of being a winemaker but like me left that behind….Maybe he should have been, because he’s got a brilliant palate. He came aboard as a cooper and has shown great strength. He’ll keep training until he retires quite frankly, but in the second stage he is learning management processes and sales skills.

He’s now the interface between production and the sales guys, working on that next stage of product development that we have to do.

He’s done a lot of external education as well; he has spent two vintages in Burgundy working in cooperages and Domaines there, he really understands that side of it very well.

He has just recently got a gig as associate judge at the Barossa wine show through the AWAC course which he completed.

At the same time William has been working at AP Johns as well, he went off and got his degree as a winemaker .

He decided to be a winemaker from when he was about 5 years old, we thought that he would grow out of that but he went on and he’s loving it.

He is still very much linking himself with the business, currently he is working at Henschke, he’s done two vintages there really learning the ropes.

He has also done a vintage in California and he is very, very happy because he has just scored the vintage wine maker gig for 2017 at Yalumba.

The cycle is turning again, it’s a very exciting time for us – it is keeping me busier than ever . If I needed any rejuvenation of my enthusiasm – I’ve got it through these guys. They are now carrying me – full of a million ideas, good ideas too. They are a joy to work with, great contribution to the business.

A very happy Peter with Alex and Will at the 125th Celebrations : Photo © John Krüger

Favourite wine ?

When I was about 25, Phillip John, my mentor wine maker cousin said to me. “Pete, if you ever want to get a truly iconic Australian wine – wherever you see it, buy Penfolds Bin 60A.” So I set out to do that.

Over the ensuing 30 odd years, without sounding precocious, I’ve bought a lot of 60A.

In the early days you could get it at good prices – not what you get it at these days. I couldn’t buy it these days at those prices. So I developed my own “Pete’s little inventory of Bin 60A”.

The reason I bring that up is that when people talk about great wines they bring with them an expectation and invariably that expectation isn’t upheld. You open a particular wine and frankly you are often disappointed for a number of reasons. Maybe that wine just wasn’t as good as you thought it was going to be…. you’ve got a cork issue, whatever it might be.

With 60A there was a 15 to 20 yr period, where Halliday and others were writing that 60A was “in the zone”.

In my experience, every time we opened a 60A, it was right on the money and the next one was even better. It is still to this day the most incredible wine I have ever drunk in my life.

Does the worldwide Cooperage business network with each other ?

My word – it’s not different from winemakers.

Do wine makers collaborate with each other ? ….sure they do.

They don’t think they’ve got some god given secret. Nothing is new in this game, its about refining, understanding and controlling what you’re doing.

Twenty or thirty years ago we were benchmarking ourselves against some guys in France and likewise they were benchmarking themselves against what we were doing .

We were learning for very different reasons for very different outcomes but at the end of the day every house has its style. Its very much about understanding the role we wish to play, assisting the winemaker, achieving the means to their ends.

But I’d have to say there’s a fair bit of science in that now.

ENDS.

Production, interview & photography : Milton Wordley

Transcript & edit : Anne Marie Shin

Website guru : Simon Perrin DUOGRAFIK

Langmeil cooper’s hands : Photo © Dragan Radocaj