Philip White : Wine writer. Stephen Pannell, our last interviewee,…

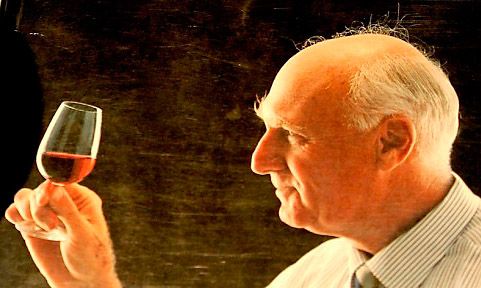

Ian Hickinbotham : Man of Wine

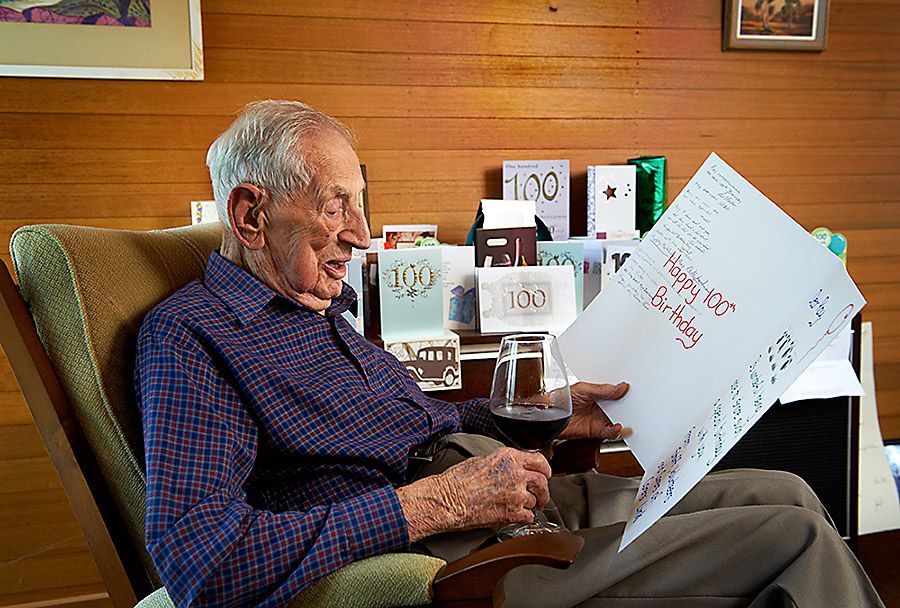

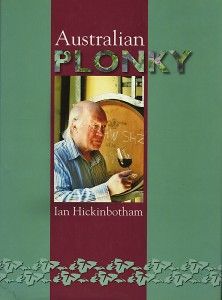

Ian Hickinbotham’s name was one which kept popping up in emails suggesting wine people for this blog. I caught up with Ian recently, he’s quite a man of wine. To quote from Max Allen’s 2012 piece in The Australian (1), “To understand what was so important and influential in what Hickinbotham did with the Wynns wines in 1952, we need a brief chemistry lesson.” You’ll certainly get that in this interview and plenty more. Ian’s life in the wine business is one of great innovation and many contrasts. He has been, among many other things, an oenologist /winemaker, wine scientist, inventor, Penfolds Victorian manager, restaurateur and wine writer. Ian was responsible for bringing the young Wolf Blass to Australia in 1961. He is now in his mid 80s and lives in Melbourne with his wife Judith.

Ian’s is a great story so the interview is a little longer than normal. Pour yourself a glass of wine and enjoy the read !

You were born in 1929 and grew up at Roseworthy where your father had founded the wine science, or oenology, course. Did you have an interest in wine from a young age ?

No none at all, I really wanted to be an architect until I found out how expensive the course at Adelaide Uni was. I didn’t know what to do, I just drifted into winemaking when I was about 17.

I didn’t go to Roseworthy Agricultural College straight away. I did it the other way, a two year apprenticeship in the trade, studied Soil Science, then sat for an entrance exam . Dick Heath, who later became Technical Manager of Hardys, was the only other person who had done it that way !

After a year at the co-operative of the Barossa Valley which was then trading as S.A. Grapegrowers Co-operative Ltd and became known by the trading name, Kaiser Stuhl, it was off to Roseworthy.

The college only had six balances in the laboratory so there could only be six students in those days.

After passing the entrance exam, I went straight into the two-year oenology course where I only just passed the final exam – I spent too much time on my thesis which excited me !

In 1949, your second year at Roseworthy, you began work on untangling the biochemical mysteries of malolactic fermentation. Early in your career at Wynn’s Coonawarra Estate you were credited with being the first winemaker to deliberately induce, manage and understand malolactic fermentation. In layman’s terms what is ‘malo’ and what effect does it have on the wine ?

Malic acid is a hard tasting acid and is the dominant acid in un-ripe grapes. By malolactic fermentation (2) – MLF as it is generally known (though it is not really a ‘fermentation’) – malic acid is converted to lactic acid, but temperature must be at least above 10ºC, which often means spring-time and it has only recently been proven that temperature must not only be elevated, it must not vary much – so modern thin walled stainless steel tanks are not very suitable !

Wine tatsing at Roseworthy College in the 1930’s : Taster in front, Ben Chaffey who founded Seaview, McLaren Vale SA, directly behind him and to the right Reg Shipster, who managed Leo Buring P/L, Tanunda : caption by Ian Hickinbotham. Image supplied by The South Australian Government.

My father was in vigorous disagreement with other industry scientists, like a couple of others at Roseworthy, John Fornachon, Director of the Wine Institute and leading scientist, Bryce Rankine, who were both actively proclaiming that MLF did not occur in Australia, because we had ‘adequate sunshine to ripen our grapes properly’.

At that time there was no testing method to differentiate between malic acid and tartaric acid: importantly, we could only measure ‘total acid’. Immediately after attaining my qualification (believing that there was not enough viticulture in the course, but pruning was part of the agriculture course in those days, which I did not do) I worked in a vineyard of Wynns for some four months when I must have come under the notice of David Wynn.

I was promoted to laboratory technician at Wynns’ South Australian winery where their fortified wines were dominantly made. It was at the rear of Romalo, the ‘Champagne’ cellar (where most of the whole industry’s brands of sparkling wines were made), near Penfolds, Magill, in the foothills of Adelaide.

After only a few months, I was moved to Melbourne as ‘winemaker’, though Sammy Wynn only ever referred to me as ‘the chemist’. This occurred as the Italian winemaker there, a man named Giacosa, had returned to Italy very ill and was expected to die. Giacosa had been sent to Australia to establish a vermouth industry and was captured on route, spending the war time interned. I was aware of his secretive practices which were probably carried over from vermouth making,

I contributed by changing the ‘hit and miss’ blending of wines in bulk for bottling just by applying simple arithmetic – and this impressed !

Mr Giacosa eventually returned and sadly I went back to the laboratory in the fortified wine cellar in Adelaide.

Suddenly, I was flown to Melbourne again where David Wynn offered me management of Coonawarra Estate Pty Ltd which he had just bought for the parent company while his father was overseas – and which I accepted enthusiastically.

Later a friend overheard David being castigated by his father for paying 30,000 pounds too much for the property, while much later the company name became Wynns Coonawarra Estate Ltd, apparently because the word ‘Estate’ could not be ‘owned’.

Coonawarra was a shock and I found the ‘squatter’ type wealthy locals quite unfriendly, probably because of the troubled history of the district’s main winery, while their own sheep industry was booming because of the universal desperate need for wool during the cold weather of the Korean War!

I was only 22 and still listened to my father a lot. Just before the 1952 vintage I asked David Wynn if I could ‘allow’ the malolactic fermentation to occur. He acquiesced, but to my astonishment, he approved the action for the whole vintage! I had meant to allow it to occur to a thousand gallons (four and a half thousand litres).

Importantly, much later we learned that the secondary fermentation occurred every year at neighbouring Redman’s winery – really because their underground tanks maintained the raised temperature (generated during the primary fermentation by the yeast) and the bacteria responsible for the malolactic fermentation are extremely sensitive to temperature and more so, to temperature change! Don Redman told me that when they told Dr Rankine this, Rankine exclaimed, “Is that a fact: is that a fact”?

When you arrived at Coonawarra in the spring of 1951, the buds of the vines had shot. How did you deal with this?

I overcame that problem initially by employing six agriculture students from Roseworthy Agricultural College, from which I had just graduated.

It was potentially a disastrous situation: the vine sap was flowing, so the vine canes could not be tied down to the trellis wires as they would have snapped. I got the six Ag students to prune – pruning being a part of their agriculture course in those days – and some very strong local footballers to tie the canes down.

My grandfather was the captain-coach of Geelong in 1886, the team that never lost a match! I was involved in football all my life as was my brother and that’s really why some of the football team came to tie the canes down.

Not sure David Wynn appreciated the footballers: he didn’t say it but you got the feeling that he thought they were a little uncouth.

After vintage in 1952 we planted 10 acres of Riesling on a vacant paddock of red soil at Coonawarra, but they all died simply because they didn’t get enough water.

I got blamed, yet I had only ever worked in a vineyard for four months! The belief has persisted among industry leaders that oenologists are also viticulturists, but many would never even have been in a vineyard! I reckon the emphasis on the importance of the vine changed though, thanks to Dr John Possingham at the CSIRO.

I don’t think he’s ever been really properly recognised; he really is one of the great unsung heros of the Australian wine industry. Though the mechanical harvester was invented in America, Possingham studied it and actually had one air-freighted back to Australia in time for the 1969 vintage. Then he taught the French how to mechanically pick grapes; nowadays, they mechanically harvest the same percentage of their grapes as we do.

Incredulously, in return they gave us their new superior clones of the classic varieties!

At that time and with the sudden growth in market and the problems with the labour market we would have never coped without mechanical harvesters. One night in the Riverland I saw one pick the equivalent of 120 pickers.

It’s rumoured that the Australian Wine Board’s tasting panel once rejected the Penfolds Grange Hermitage for export on the grounds that the wine was volatile. Is that just an industry rumour ?

I went into that a few years ago with Brian Miller. I came to the conclusion that was an industry rumour. I knew Max Schubert fairly well; he liked some volatility in dry red wines and so do the Europeans. He even went to the extent of leaving the bung out of the barrels to increase the volatility.

When I was in that laboratory at Romalo in Adelaide, Max used to turn up with samples and he’d want us to tell him if we thought the volatility was excessive.

Max was a very generous man, I liked working with him and later sold him bulk wine when managing S.A. Grapegrowers Co-operative Ltd for his ‘Bin’ series wines.

In the early days Grange was rubbished in Adelaide.

Max gave me the job as the Victorian Penfolds manager to try and introduce it to the Melbourne market. It was always recognised as the dominant Australian market for Dry Red.

Judith and I drank 6 dozen bottles of Grange with various people in the trade.

It slowly took off.

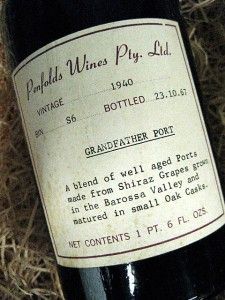

It’s a bit of a sore point with me; I really put Grange on the map in Melbourne in 1964 (Sydney was supplied the alternative top wine of the time instead – Grandfather Port), but I’m not often credited with it.

I was with Penfolds for less than two years and in those days we mostly sold fortified wine: table wines really hadn’t taken off.

When did it become fashionable to drink table wine in Australia ?

From what I have read, and I believe it to be true, history says whenever a community or civilisation becomes prosperous it turns to food and wine. Australia was becoming more prosperous.

A big factor in this story was the influx of war-torn Italian immigrants that helped a lot. The Italians didn’t want to buy bottles. Bottles were too small, while I suppose in Italy they made their own wine. I seem to recall in Victoria they brought a law in allowing people to make up to 400 gallons of wine at home.

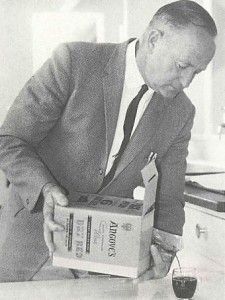

You worked on developing the table cask, was this what started it ?

The trend away from bottles was the background to how Angoves and I worked separately on the table cask. I designed a table cask on the basis of a household brick, length is twice the width and one and a half time the height. The same measurements pertain today.

I did that while I was with Penfolds. I gave it to them and they just ignored it.

A few years later 70% of the wine we drank in Australia came out of a cask.

You were once quoted as saying “Pasteur was wrong, and that the Australian oenology is probably — not possibly — the best in the world ! I actually ponder if our wines are too clean now.” How do you see both of those statements now ?

I think some wines now are too clean, but I suppose the commercial ones have to be. Filtering is so good now you can filter out all bacteria.

On my son Andrew’s advice, I looked up malolactic fermentation (2) in Wikipedia, and there is the phrase that Pasteur was wrong. Pasteur declared, when bacteria were present, I still remember the phrase from my thesis, ‘Le mal existait’.

In the 1950’s a great deal of dry red table wine was undrinkable because of intense bitterness of taste. What did the addition of sulfur dioxide do to fix that ?

Once I encountered a million litres of dry red wine in that bitter condition! I saved a tank of the wine by removing it from its lees (racking), added tartaric acid (to lower its pH) and sulfur dioxide (to nullify the bacterial activity) and clarified the wine using dissolved gelatine which attached to much of the bacteria and slowly settled to the bottom of the tank.

I was then able to filter the clear wine off those gross lees! pH was everything, but I’d need another book to explain that. (3)

I treasure the thank-you note Ray Beckwith sent me after his pH doctorate. I often think he did as much as Max Schubert, but never got any of the accolades.

Eighty years ago 25% Australia’s wine was diseased, Beckwith saved all that. What’s that worth to an industry ?

You brought Wolf Blass to Australia, how did that happen ?

It was all to do with Sparkling Rinegolde’s phenomenal growth in the early 1960s . Early on it sat at 20% a year; cash flow was a nightmare.

Sparkling Rinegolde was actually a Leo Buring Pty Ltd product. We made it for them at S.A. Grapegrowers Co-operative Ltd where I worked, which later traded as Kaiser Stuhl. The naming of the wine was almost a comment about Australia’s cultural cringe back then. I saw it also when we introduced the name Kaiser Stuhl, it went like wildfire. Sydneysiders thought it was German.

Before they knew it was actually an Australian wine, they loved it.

I couldn’t get an Australian winemaker. Cooperatives had a reputation for sacking executives. I went looking for one through an overseas cooperative in London.

They interviewed Wolf, he looked good and I took a gamble. Wolf worked with us on sparkling wines, I reckon we taught him that malolactic fermentation softens the wine (2).

Wolf had a very good palate. He is a great marketer and read the Australian market very well. He was right about Langhorne Creek.

As you know he went on to form Wolf Blass Wines a few years after he arrived here.

For a decade you ran Gini’s Restaurant in Melbourne, wrote for The Australian Financial Review, The Age and Epicurean. How was that period of your life ?

For some time I couldn’t see any future in the wine industry. We really did not want to run a restaurant. I was front of house at Gini’s and Judith an ex-nurse managed it all, she was ideal.

Ian and Judith at home recently with the family portraits. Jenny, Andrew and Stephen. Photo : Milton Wordley

I wanted to teach people how to taste wine like I’d learned at Davis University in California, but to do that I had to have a licence.

For a while it was French downstairs and Indian upstairs. Funny mix but the first in Australia.

Restaurants are hard work and not worth the bloody time.

During that time I wrote for the Fin Review and The Age.

I got involved in wine writing after I wrote an article and submitted it to the Fin Review, the sub-editor liked it and took it to the editor.

The editor said this bloke can write and I got a job. I tried to be neutral, I didn’t want to write about individual wines as I would have been criticising my oenologist ‘mates’, indirectly. I wanted to write about wine in general. Wrote for them for at least 10 years.

I didn’t find it easy, dealing with a new subject every week.

One day they told me to write reviews, but I felt I couldn’t do that. Ethically as a wine maker I felt I should not review. They read the riot act to me and so I got sacked!

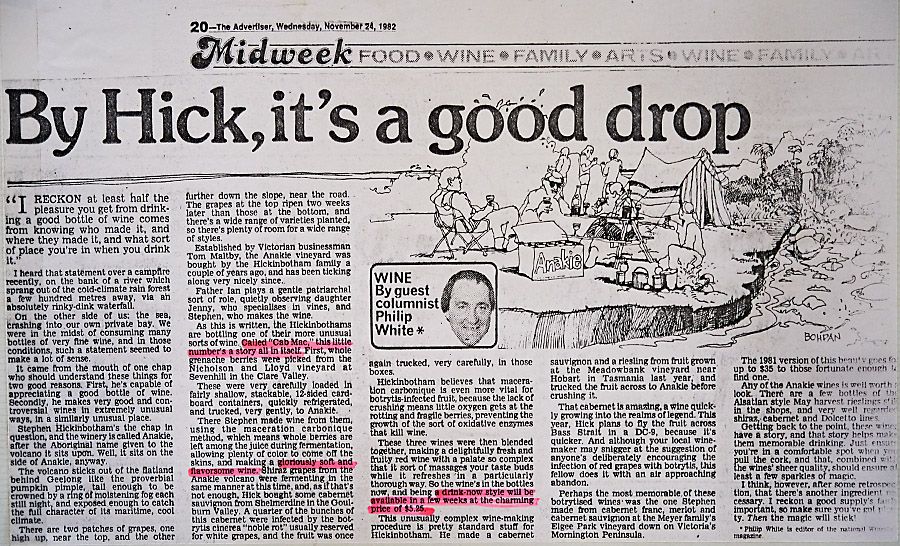

Mark Shield and Philip White were writing as well in these days, I enjoyed their work.

The Mornington Peninsula is a special place to you. Why ?

We, the family, leased a winery just outside of Geelong and set up the Anakie winery/vineyard. I think that was in the early 80s. In my opinion the region doesn’t get enough rain, it’s in a rain shadow.

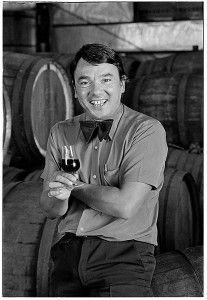

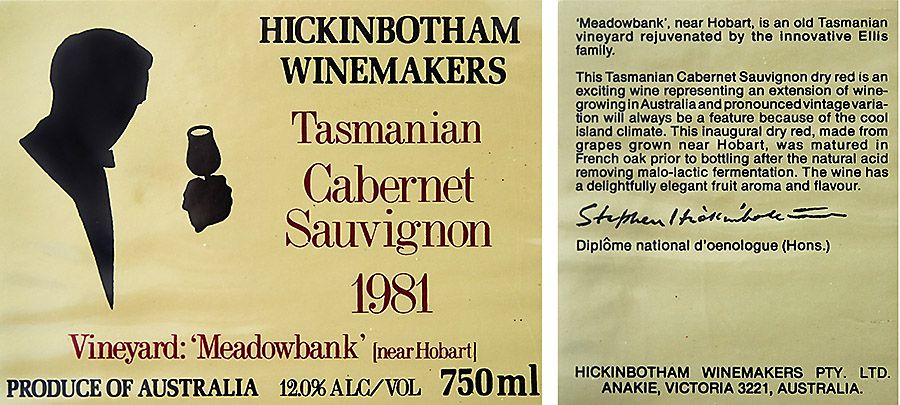

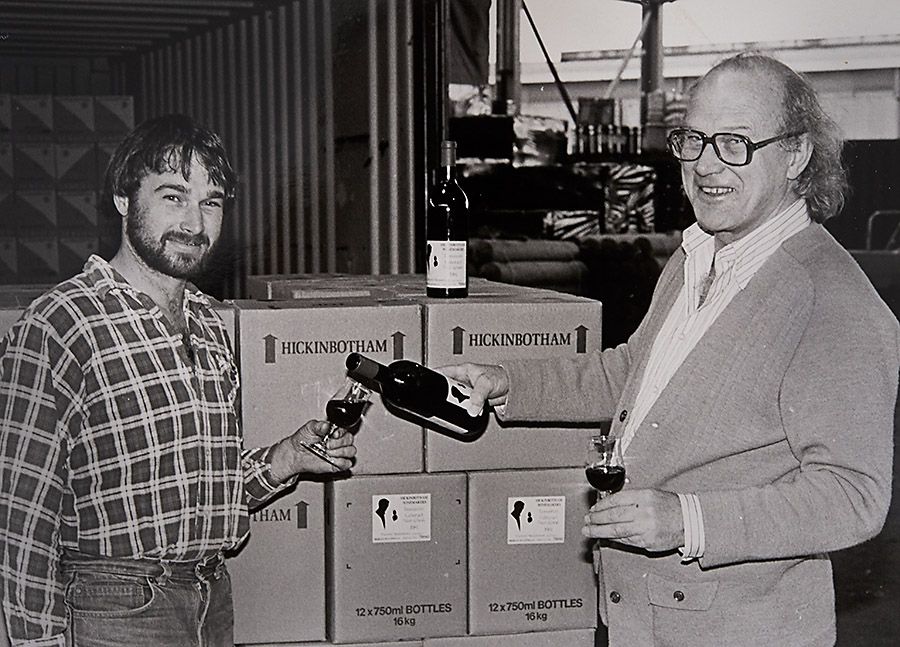

Ian pours his son Stephen a glass of Meadowbank 1981 Cabernet Sauvignon to celebrate the first shipment to New Zealand : Image supplied

We made and bottled other people’s wines, many from cool climates, like Ballarat, Gippsland, Western Districts and Mornington Peninsula. This spurred our enthusiasm for cool climate wines. We went across to the peninsula in the late 80s.

Stephen (4) had just come back from Bordeaux in 78, Jenny had been the first viticulture apprentice at Sturt University and Andrew studied viticulture in Burgundy: we were all keen on cool climate wine.

Back in the early 80s we also used to get fruit from Tasmania, we were among the first. I reckon we would have set up down there, but I was afraid of the wharfies controlling our shipping to our main market in Sydney.

Second son, Andrew, took friends to Tasmania to pick grapes. We once had 40 pickers pick at just the right time. That night, the flight was cancelled and we lost the lot.

They are getting some very good fruit there now. I reckon this climate change is real.

Favourite wine styles or memorable wines?

Pinot Noir and Chardonnay.

I used to belong to rather an elite club in Melbourne (‘The Ritz Restaurant Club’) where I learned a lot. We tried some great wines over the years, especially Burgundies, Maurice O’Shea’s, etc. I can still remember the 1943 Yalumba Cart Dor. It used to turn up quite often.

Pinot Noir, the difference ; French and the New World ?

The French are a bit more “dirty”, go back to what I said a minute ago – we are too clean.

Andrew taught me something : the famous French Professor Peynaud of the Bordeaux University, once said to him ⎯ moulds and wild yeast contribute to the ultimate wine. That means, even mould on the grapes. And I’m not talking noble rot.

Did you ever have an involvement in the Hickinbotham vineyard in Clarendon ?

Not really: that was my brother Alan’s venture. I told him to go to Clarendon not McLaren Vale, it’s cooler up there. I steered him to talk to Dr Possingham. I think Poss helped him with the planting.

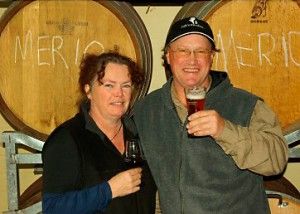

Katie Jackson with David Hickinbotham at the Claredon vineyards, the day Kendall Jackson bought the vineyard. Photo : Milton Wordley

Anything else you’d like to say ?

I will say Australian winemakers are probably amongst the best in the world. pH dictates the well-being of any wine.

Our sons Stephen and Andrew went to universities in France, Andrew to Burgundy and Stephen to Bordeaux. In France pH was deemed not to be important. I remember one Christmas in 1978 Stephen and I talked for five days, he really knew nothing about pH; he didn’t think it was significant.

Foot notes.

(1) : https://www.theaustralian.com.au/life/food-wine/vintage-years/story-e6frg8jo-1226386514039

(2) : Malolactic Fermentation. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Malolactic_fermentation

(3) : Acid in wine. Now it is recent knowledge that if the bacteria that convert the ‘strong’ malic acid to soft-tasting lactic acid are left in the wine, that is, the wine is not removed from the bacteria or vice versa, those bacteria, depending on the type (needing food – if you like) can proceed to consume other natural components of a wine ⎯ like very desirable glycerol (which we know as ‘glycerine’). It can be about number four quality component in dry wines, after water, alcohol, tartaric and other acids. A consequence can be – wine that tastes so bitter it is undrinkable, due to development of acrolein from glycerol (and the condition is defined as the disease, “amertume’ by the French). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Acids_in_wine

(4) : Stephen Hickinbotham, Ian and Judith’s oldest son and a very talented wine maker was killed in a plane crash in 1986. https://www.winegenius.com/in-memory-of-stephen-hickinbotham/

(5) : Kim Brebach’s piece on Ian in his ‘Best Wines under $20’ site https://www.bestwinesunder20.com.au/ian-hickinbotham-restless-genius/