Champagne is the international drink of celebration. As someone involved…

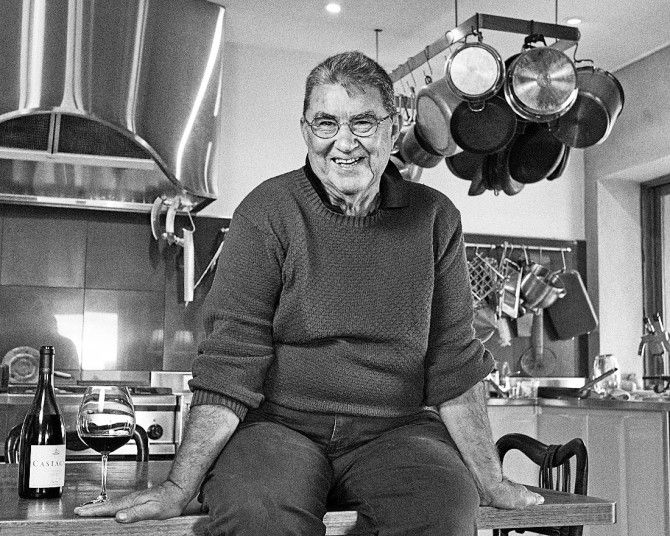

Julian Castagna : Castagna Wines Beechworth

Whenever we travel overseas, we always take along wine for our family and friends. We usually take Australian sparkling shiraz, as you don’t see it much in other countries. This year we took along Castagna Sparking Genesis Syrah, made by Julian Castagna. It’s one of our favourite sparklers.

Julian had been been involved in the media industry for over 40 years. His journey from filmmaking to the wine business is a fascinating story. And along the way he became increasingly involved in biodynamic viticulture.

Julian lives with his family at the winery at an altitude of 500 metres, five -and-a-half kilometres outside the beautiful town of Beechworth in Northeast Victoria, high in the foothills of the Australian Alps. His son Adam works with him at Castagna and has his own label ‘Adams Rib ‘ ; his other son Alexis has returned to the film business and is a director of photography in Sydney.

Julian is a member of the international group known as Renaissance des Appelations/Return To Terroir. Castagna is one of only five (Jasper Hill, Cullen, Ngeringa, Cobaw Ridge) Australian winemakers who are fully certified by Renaissance.

Here is his story.

You came to wine after a successful career in film and advertising – Why ?

I came to wine because I got to a point in my life where I was becoming bored with what I was doing. I was sitting in meetings where they were paying me outrageous amounts of money, but they weren’t listening anymore.

Advertising seemed to have reached a point where the research people were more important than experience and instinct, more important than the art of it.

I sat thinking, ‘this is going to be disastrous soon, I’m not enjoying it any more, it’s going to kill me if I don’t stop and very soon they are going to stop offering me work, I have to stop this.”

So that’s what I did. I just stopped.

I only knew two things well. I knew film because that’s all I had done – all I had ever wanted to do, and I knew a little bit about wine because wine had become an obsession which started during my time in London.

I had lived in London for many years and was there when wine was plentiful and reasonably priced. I became obsessed with it.

Also my life in film in Europe had taken me to many European vineyards and I had had the good fortune to taste much of the best that the world has to offer.

So on that day I came home to my wife Carolann and said “I’m going to stop”; to which she said ‘That’s really good but what are you going to do?” ; so I said, “You’ve got a horse, how about we buy a bit of land and I’ll try to make a bit of wine – and we’ll travel. This house is worth quite a lot – we should be alright!”

This was about 1995- 96 – we bought the land in ’96 and we started here in ’97.

Strangely enough I wasn’t intimidated by the technical aspects of wine making; from my time living in London and my experience in visits to wineries I formed the impression that making wine didn’t seem to be brain surgery.

It seemed to me to be more about what grows rather than how it’s made.

Most people I met during that time were very generous both with information and hospitality – I was a film guy who loved wine. They would talk to me about what they did and how they did it, give me wine, take me to dinner. I loved it.

All the people that I really admired didn’t seem to have the ‘I’m a hero winemaker’ attitude.

Too many wine makers really believe that what happens in the cellar is what it’s all about – they seem not to take in to account the crucial-ness of what happens in the vineyard; they kind of do, but with some at least, I get the impression that the vineyard is a necessary distraction – what happens in the cellar seems to take precedent.

I participated in a wine show called ‘Rootstock’ in Sydney about six months ago – it’s ostensibly about natural winemaking and not one person asked me about the vineyard – not one…!

They all asked me about what I did to the wine: Did I add sulphur? What vessels did I use? Etc. That stuff is important, but secondary. No one asked me about the vineyard; about the nourishment of the land; about how and when to ‘move in’, and how and when ‘to step back’ and watch.

This is a show based around sustainability and vineyards: it should be mostly about how it’s grown rather than how it’s made.

Why Beechworth ?

If I was going to make such a dramatic change in my life I wanted to make sure that I had the chance to make a wine that would be thought of seriously by serious wine people.

I guess because I learned wine in Europe and think that wine should be medium bodied and food friendly there are only a few places in Australia that have the potential to make, what equates to me as world class wine.

Beechworth is one of them and it is among only a handful of places in Australia, perhaps even the world, that tastes of itself, meaning that it has a character which is unique and always tastes of itself.

Leaving Sydney was a huge wrench, I was brought up in Melbourne and I ran away from Melbourne before I was 20 and only returned to Australia after ‘finding’ Sydney, so I really didn’t want to come back to Victoria – but the more I looked the more it seemed that Beechworth had huge potential and was unique.

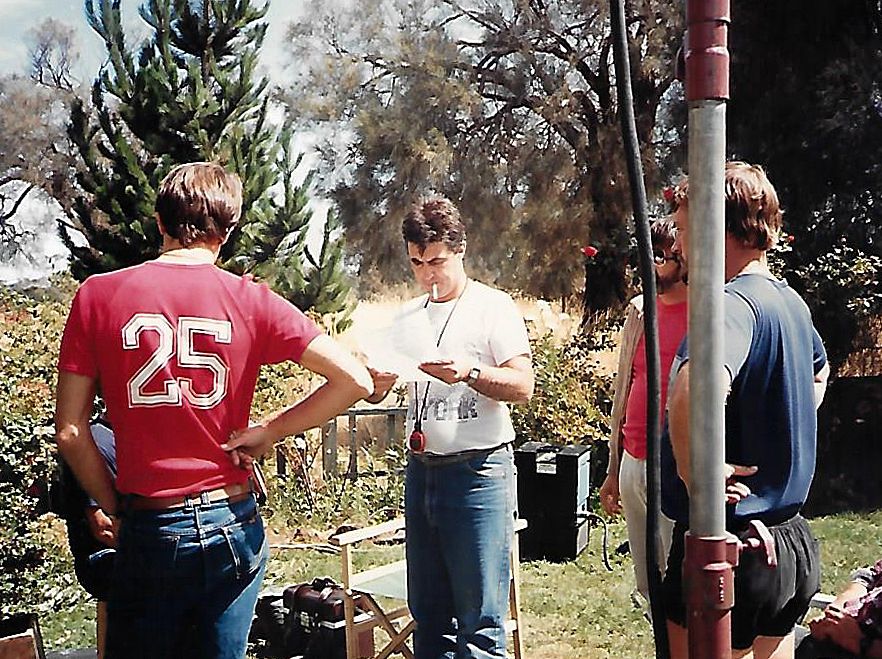

How did you come to work in advertising and to be in Europe ?

I joined the ABC in Melbourne, as a gopher – and I gradually grew up.

One of the things about the ABC at that time was that they didn’t have many young people on staff, but they had screen time – remember how they used to play the test pattern to fill time. So a friend and I invented a fill-in program to fill one of those holes. It was called ‘The Hit Parade’. We made it up, with no budget and the goodwill of those around us.

We had a presenter who would play the hits of the day and we would interrupt him by throwing comic voices at him.

Somebody saw the show when visiting from Sweden and said, “Would you like to make it in Sweden?” and we said “Yeah, yeah, of course!”

What we didn’t realise was that it was the people around us that did all the work.

We did a bit of thinking but the crew did all the work getting the cameras in the right place at the right time, being ready for the jokes. In Sweden of course – the crew did nothing that they weren’t asked to – they said, “You tell us where you want the cameras, tell us what you want.” So, it was a total disaster and didn’t last very long at all.

This was in ’67/’68 and we went from there to Spain. We got a bus from Stockholm to Alicante.

It was the assuredness of youth, really. We were stony broke, the job in Sweden was a disaster!

What to do ?

The Americans were making films in Spain – think the Clint Eastwood spaghetti westerns! We will get a job with the Americans!

From Alicante we spent our last money on the taxi fare to the place we were told where the Americans were working and when we got there it was just a ‘lot’ – there was no studio, just sand.

Totally broke we hitchhiked to Madrid – which took three days. I got a job teaching English to keep body and soul together.

Then, an American guy we ran into who was starting a film production company was looking for help. He made advertising films. I didn’t really know anything about advertising, but he paid good money so we went to work for him.

In those days the person who had most say on advertising shoots was the agency producer and during one particular shoot the agency producer and the director, who we were working for, had a punch-up and the producer fired him, on the spot. Then he turned to me and he said, “you’re a director aren’t you. …well you can finish this now!” That’s how I got into advertising.

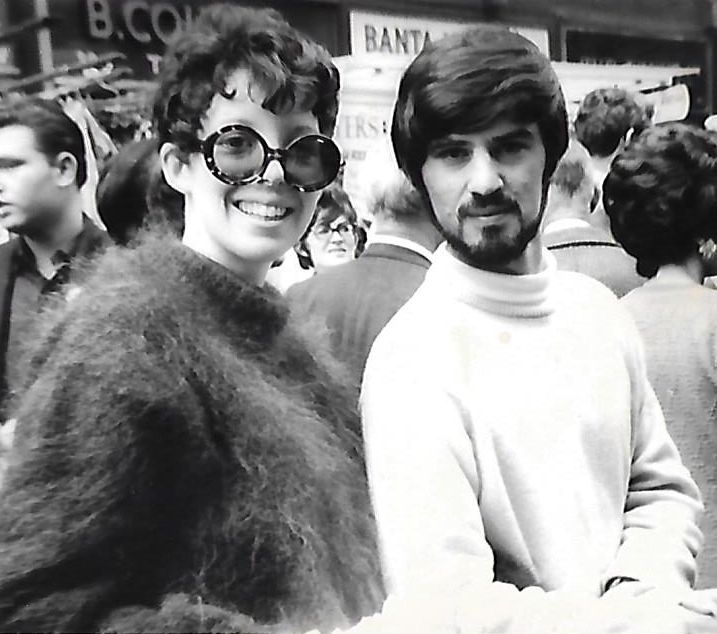

Did you have an interest in wine then ?

Sort of…my parents were Italian and always drank wine with meals – meal time in our house was a ritual really.

My father had wine that was undiluted, my mother slightly diluted and then the children depending on their age had wine and lots of water.

Serious wine really came in London. It was about 1971.

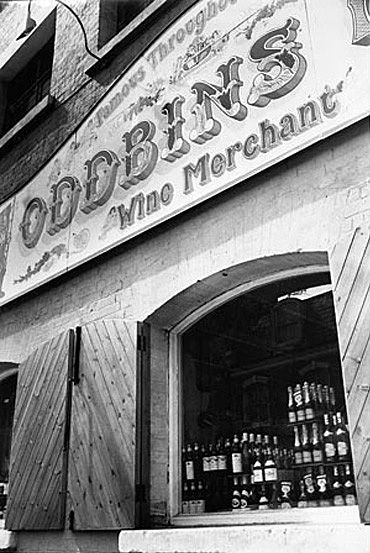

One of Carolann’s girlfriends was married to a guy called Ken Norman who was the manager of the very first Oddbins in Monmouth Street in London – when they really were bin-ends.

Beside his Oddbins job he was also a trader in wine, and regularly showed me liquid that I had no idea could be so magic.

I knew immediately that I needed to learn more about wine, but I had no money to play with because I was doing any dogsbody job offered till I could find work in the film industry. At that time you had to have a union ticket to get a job and you had to have a job to get a union ticket ! Not easy.

Ken Norman did much to help me learn. I would tell him what I could afford and he would sell me wine – always well chosen.

I started out spending about 50 pence per bottle because that was all I could afford. This was the time that Oddbins really did sell ‘Odd Bins’ and I got to taste a whole lot of strange stuff. But I got serious and Ken would also show me great wines.

He had a huge quantity of wines in the catacombs where much of the trades’ wine was stored those days, under bond. Which meant you didn’t have to pay tax for the wine till you had officially bought it.

And you hadn’t officially ‘imported’ it till you’d paid the tax. We’d go down there on the pretext of tasting wine to see that it was okay – so he could drink wine that had no tax on it.

The deal was – I’d take a loaf of bread and a bit of ham and cheese and he would open something amazing. I seriously caught the bug.

I bought every book about wine I could afford and started buying wine.

Sometimes the bigger players wouldn’t sell to Ken because he was a trader, and I guess pinching their customers, however, they would sell to me. So I would buy wine for him and as payment he would give me wine. I remember the first one he gave me was Chateau La Lagune 1962 – a third growth Bordeaux. I got given two cases – it was the first serious wine I owned. It drank beautifully over 20 years.

I eventually got a job in film, a job I suspect no one else wanted, but it got me a union ticket and that got me back into the film industry.

Did you have an interest in viticulture or wine ?

Wine …..the interest in viticulture came later.

When we decided to change our lives and bought this piece of land we were quite naïve and not very knowledgeable about farming. We got lots of advice from the people around us; how to clear and prepare the land, where to put the vineyard and what to do and how to do it.

And for the most part we were grateful for the advice.

We planted our vines and looked proudly at our handy work, but almost immediately the vines started to look sick and we didn’t know why.

So I asked ‘an expert’ who said, “It’s really simple, it’s the African black beetle, it’s in the soil in this area”. “Does that mean that all of this is for nothing ? That it’s not going to work ? ” I wanted to know.

They said, “No, no – you just have to kill the beetle”. I was given the name of a product that would do the job; so off I went to buy it – then I read what it said on the label!

The container had a very prominent skull and crossbones displayed and the instructions said if you are spraying it and it gets on your skin, get off the tractor and go and have a shower…. wear a full body suit…. and I thought, ‘This can’t be good. My intention is to make one of the great wines in the world and I’m about to destroy the soil. No way!’ There had to be another solution.

I knew a bit about biodynamics, through meeting growers, mostly in Europe… but it hadn’t clicked that it could be a complete way of farming. We were always going to be sustainable, whatever that meant, and we had no intention of doing nasty things to the soil.

Fortunately I was still making films, documentaries and advertising and so I had the opportunity to travel. I got on an airplane and went around the world and talked to anyone who would talk to me about sustainability.

Suddenly I met all these amazing people – one of them was James Millton from New Zealand – he has been a really powerful influence. I spent five days with him, and he enthused me about the possibility of biodynamics. He wrote me a five-page letter which I still have, and we refer to it to this today.

It was about his understanding of biodynamics and how biodynamics can work – not how it does work but how it can work. All of it made sense – I came back and that’s what we did.

The black-beetle-problem had a really simple solution. The black beetle likes to eat the roots of grass. I had been advised to clear the grass from the mid-rows to better grow the vines. As soon as the grass was allowed to grow back the beetles tucked back in to the grass roots – vines were left alone – problem solved, sans nasties.

Biodynamics seemed very interesting so I searched out biodynamic people here in Australia, found the Association and got involved in that.

Who are the people back then in Australia that influenced you ?

In terms of viticulturists no one.

I think I was the very first one who said ‘biodynamics is about the quality of what you grow rather than only saving the earth’. I wanted to grow fantastic grapes and saw very quickly that biodynamics made a difference.

It seemed to add a life to wine that I had not seen before – even wines that I didn’t like, still had that ‘alive quality’, which was really interesting.

The first biodynamic tasting I went to – of about 100 growers in Bordeaux – really opened my eyes in a way that I hadn’t experienced before.

That was in 2003.

Erinn Klein : NGERINGA Wines , the Adelaide Hills.

By this time I was asked to be part of Renaissance, ostensibly a group of the world’s best biodynamic grape growers.

At that time only Ron Laughton and me were invited to be members – then a little latter Vanya Cullen was invited and later still Erinn Klein, then recently Allan Cooper, so there are only five members in Australia and only one in New Zealand.

How did biodynamics come about as a movement in Australia today ?

Part of the problem is that biodynamics has lost some of its lustre.

It gets labeled as voodoo science. It can be difficult. You have to make the effort to educate yourself.

This has caused many to move to ‘natural wine’, which often consists of growers who may farm conventionally but then don’t put sulphur into their wine, then think it is okay to call it natural ! It’s a real problem, and I think is causing confusion in wine buyers.

After my experience of the tasting in Bordeaux I thought it would be really good to bring that sort of experience to Australia. I was Chair of the Biodynamic Association at the time and I suggested that I wouldn’t mind organising a really serious symposium on biodynamics here in Australia.

They said okay and gave me some seed dollars as a working capital. They employed someone to help me who was a great organiser. I thought it out and she made it happen.

Return to Terroir tasting in the Melbourne Town Hall. Julian organised it in 2015. Photo : Milton©Wordley.

It was held in November 2004 here in Beechworth. I invited everyone whom I admired and also some I didn’t who had really great information to impart – to be presenters.

So, we had two days of talking about the practicalities of making wine with fruit grown biodynamically, and then we tasted the produce.

Lots of people came. Lots of eyes were opened; people came from all over the world. We had presenters who were esoteric and others who were practical farmers; beef, orchardists etc.

They all told the same story from different perspectives.

The Castagna Family. Photo Philip © White, Drinkster.

How has your background in media and advertising effected the way you market wine and organise conferences ?

When we first started we were selling mostly by mail order and almost no one else was at that time…now everyone is. My attitude has always been, both in selling and in teaching: ‘Tell the truth, and let people work the rest out for themselves’.

We don’t generally send wine out for review because we prefer to taste wine with the reviewer, which can be difficult for them – which means we are not reviewed as much these days.

You said you don’t enter wine shows but you did enter the Provenance class at the last Melbourne wine show ?

We don’t usually but let me tell you how it happened…

2011 was a very difficult year. I hated what we made – the wines just didn’t taste like Beechworth, didn’t taste like Castagna – I decided that we would release nothing.

For someone at our size to destroy a whole vintage is a pretty complex thing to do.

I also thought that if I left it in barrel, in a year they would be better, and then money would become a criterium and I’d say – “Well it’s not so bad is it?’

I was not going to put myself in that position.

So I thought fuck it, I’ll turn it into alcohol – I wasn’t sure what I was going to do with the alcohol but, I thought, we’d see. We found someone who could distill it and they sent me back three barrels of alcohol. It wasn’t horrible! It wasn’t bad! In fact, it was quite good.

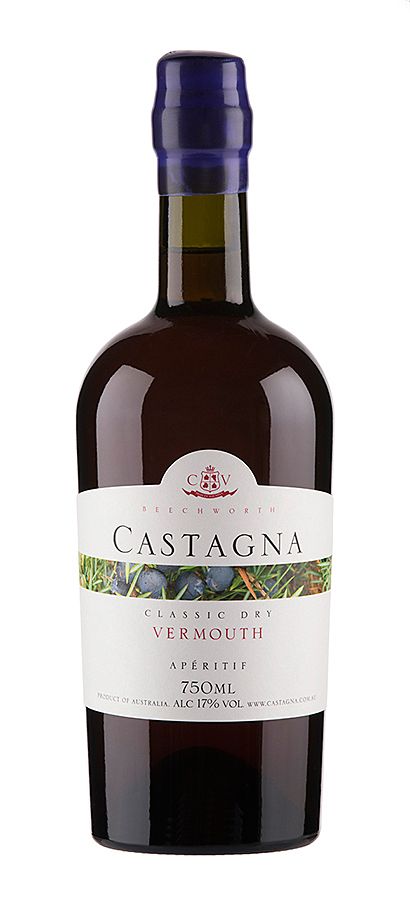

I hadn’t a clue what we were going to do with it – I just left it for a while to get some barrel age. Then I thought of Vermouth. Gilles Lapalus had started making a Vermouth which I thought was quite good and interesting, and I quite liked. I remembered in London tasting a Vermouth which I really liked but had never been able to find again. I thought, “I wonder if my memory will be good enough – let’s have a go”.

So Adam and I spent about two years buggerising around with wines and herbs, alcohol and sweetness and it seemed pretty good. We made a large’ish batch that I thought was pretty interesting. We showed it to a few people and everyone seemed to like it.

Adam said, “I’d really like to put it in a show” – and I said, “We don’t do shows Adam!” To which he came back with, “How will people know about it? Vermouth is out-there, not like wine.”

Coincidently, I received an email from a major Melbourne show asking my opinion on introducing a Vermouth class. So I wrote back and said, “Yes, I think it could work. It could be interesting.” They wrote back saying, ‘Well, are you going to enter?’ I said, “No, no, we don’t enter shows.” But then I thought, ‘That’s stupid’. So I said okay!

They also wanted me to also enter some of our wines. And I thought…’I’m not sure! It’s such a lottery…’ But then thought, ‘Okay…let’s try it this once’.

The Provenance category seemed to me to be to be a worthwhile one. I had always tried to make wines that drink well at the beginning of their life but also have texture and length and last for a long time. So I thought, ‘Just do it. Just shut up and put it in.’

We put in Genesis from 2002, 2006 and 2012.

And were delighted with the Provenance Trophy.

But if Adam hadn’t pushed me to enter the Vermouth – which also won a trophy – I don’t think I would have entered anything.

The moral is: Listen to your off-spring !

On your website you refer to true wine — what do you mean by true wine ?

What I mean is wine that represents the land. I think what makes wine special is growing the right variety on the right piece of land.….truth is about getting that right and then not mucking it up in the cellar.

How did you come to grow the varieties you’ve got here ?

I was lucky. I wanted to look at making the type of wines that I loved.

Bordeaux was what first got me excited about wine, then I found Syrah and Sangiovese and Nebbiolo then Pinot. When we were looking for land, I decided the two areas that I thought could make great wine were Margaret River and Beechworth – I didn’t want to live in WA, so we bought this land.

The land seemed to me to be ideally suited to Shiraz so we decided that’s what we would plant.

Then that same year, I went to Italy and came back to this special piece of land and thought,

‘This a bit like parts of Tuscany – I should grow Sangiovese!’ And that’s how it started.

Shiraz was always going to have a little Viognier in it because that’s what I liked in the wines of Cote Rotie.

I also knew that I didn’t want to grow clones…. I got my stock mainly from South Australia and a bit from Victoria.

Best’s Victorian vineyard Shiraz. Photo : Milton©Wordley.

I searched out and found people who had vineyards with progeny from the 1850s material that had been imported into Australia from the Rhône Valley, and which we are so lucky to have. I went and tasted fruit at harvest – people were very generous.

Rick Burge, Burge Family Winemakers.

I got cuttings from Jones vineyard and from Hardy’s, and some fruit from Rick Burge’s Draycott vineyard, and then we took some from Best’s Victorian vineyard as well, the really early stuff from Great Western – so our vineyard is based on those 4 varieties.

There is a tiny bit of PT 23 but everything else is from those 4.

When I asked for cuttings everyone was incredibly generous, very kind people. Some charged me, some didn’t. They said ‘They’ve got viruses. You should think about planting material that’s been cleaned up’.

And I said, ‘Humans do, too. I can only go on what I taste.’

We very much trust the land and the season…if you like, we put our faith in it!

This year’s vintage was really incredible, we had Shiraz, Sangiovese, Viognier and Nebbiolo all picked in the same week and all before the start of autumn.

It was just crazy…manic! It was 40 degrees all the time! The problem was, how to prevent fermentation starting early…to get some cold-soak time ?

Every vessel was full…EVERY SINGLE VESSEL!

From a practical point of view there’s been a major change for us after 2014 because up till then we didn’t net – but that year we lost 60 % of fruit to birds. So we bit the bullet and netted. A big investment and a big job … (“it binds the family together”, jokes son Adam)

Does Adam your son take your advice and does he heed it ?

What I hope that I have passed on is that detail is everything.

Don’t do something tomorrow if you should do it today. I probably haven’t said those words to him but it’s how we work.

He’s going to take it over and I think that the wines that are coming out of him are interesting.

What do you think about that Adam ?

The truth is that I’m the physical component to his mental.

So when I am making an Adam wine – he is my on-call consultant…. maybe on call more that you would like.

But when we’re making everything else, he’s the winemaker (although he hates the term), and I’m his arms and legs and his assistant.

We do everything together.

I’m in that lucky position where I’ve got this wealth of knowledge to draw on that only a crazy person wouldn’t utilise.

Often we disagree and we both need to blow-off steam, and we do it at each other. There are times where it is near walking-out-the-door time for both of us, but we both take an hour or even an overnighter, and then we’re back on and it’s all good.

It wasn’t always like that. I don’t have a great relationship with authority to start with, so having my dad as my boss has been challenging. But I get to have the best of both worlds.

I get to be a young winemaker in a region which has finally understood that young winemakers are coming through. Then I get to have all the knowledge of all of the older winemakers who have been tasting wine since the beginning…of awesome wine coming out of this country. I get enough movement to have bit of a play with some really interesting stuff. You know we’ve got Riesling on skins in there, and we’ve got ‘Harlequin’ here and we’ve made cool Vermouth.

So it’s a lot of fun.

It’s a lot of hard work, and this time of year it’s insane –up at five home around midnight – that’s if you get to go home at all !

Vintage is always busy, it’s always difficult just because we are on all the time.

But when a normal vintage or as normal as you can have in this country comes, it is different. Ten years ago in 2006, we picked over the course of nearly eight weeks and this year everything came off in four days! On the fifth day we did some serious sorting of Nebbiolo. To have that happen means that you are on 20-hours a day for three days before it kicks off, and then you are on a 24- or 36-hour clock.

Everyone gets punch drunk.

You are kind of used to being able to let it cold-soak for a few days, and then have everything come on bit-by-bit…hasten slowly

But this year everything came in, and for the next ten days it was no more than two degrees off of 40 degrees, even at night it was only getting down to 27 or 28. I need wine at that point or below. It was just a matter of shifting it through cooling, you know, get up…. cool this…. cool that… move this.

Julian…

Cooling is very important……which is why I want to reserve judgment on this year’s harvest.

It looks fantastic at the moment, but it was very hot during harvest and I’m not used to that. The fruit didn’t have as long a cold-soak time as I should have liked.

Adam…

It’s going to be a delicate season – the smells coming out of the tank at the moment are delicious – it may be soft, but delicate would be the better description – a soft- touch vintage…mmm…intriguing ?

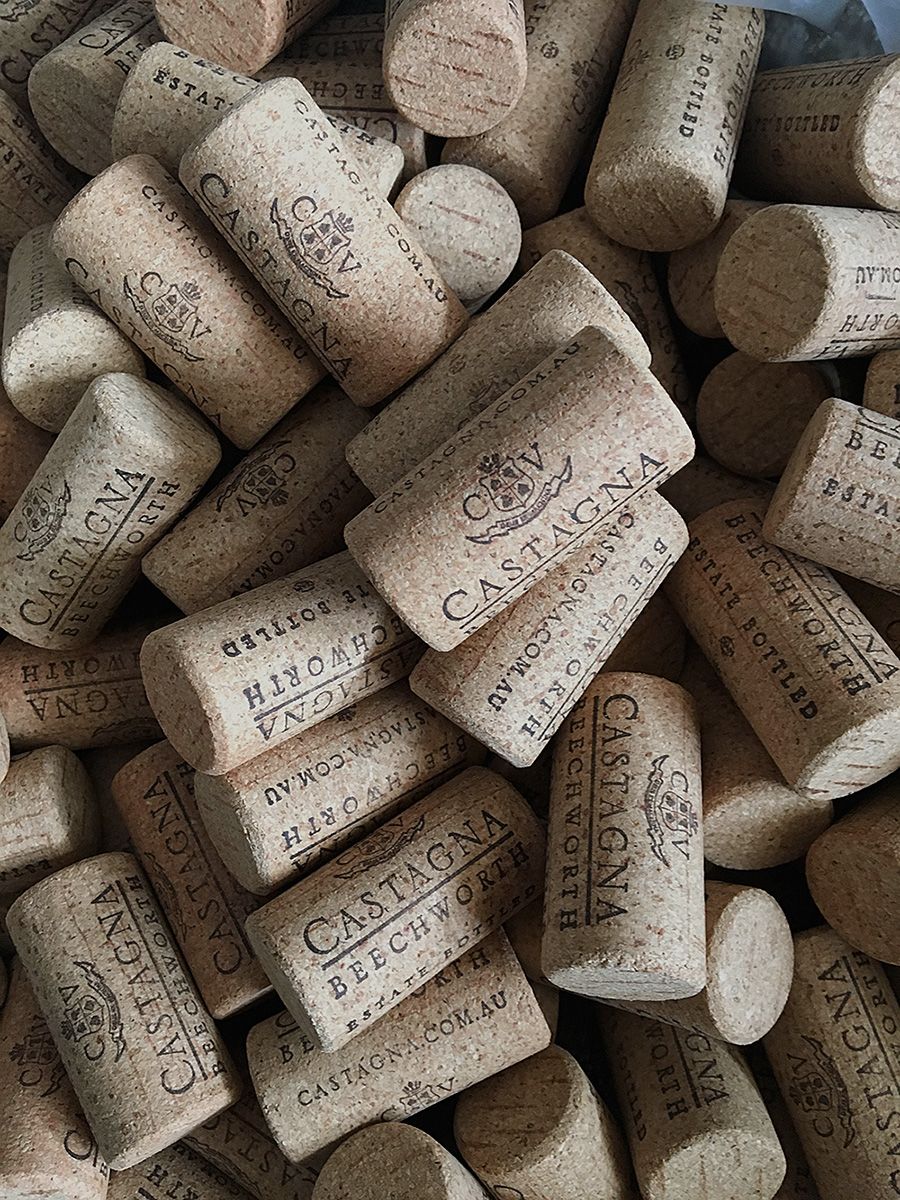

Julian, I thought you might want to say something about closures …

It’s a complication.

Wine is more than a commodity. For us, people who work in wine, closures are simply that, a way of sealing a bottle, but for many of our customers they are a joyful process to opening a bottle.

The process is part of a tradition, it is part of the process of enjoyment. It is part of a culture of wine.

It may change in time but at the moment for me cork is best… I have no problem with what screw-cap does technically – the problem I have is that it takes away the process. It takes away the theatre, it turns wine into a beverage. It’s akin to taking a stroll through a forest as opposed to driving, one is much quicker and easier, but nowhere near as rewarding.

So I went to the best solution that we could come up with and that was DIAM. We went to DIAM in 2003. Prior to that I was using corks that were costing us $1.60 to $1.80 each – hand selected, they were the best corks I could buy, and yet I was still losing 5 %.

Since we have gone to DIAM I have not lost one bottle.

Having said that, I don’t have a problem with screw-cap, the problem I have is the emotional connection for drinkers – those who aren’t specialists. That may change in time. There is still some small doubt about DIAM long-term – maybe in 20 years plus; but if it becomes a problem I’ll recall the wines and re-cork.

I’ll put out an advertisement and say – If there’s a problem, I will re-cork it at our expense.

ENDS.

Production, interview & photography : Milton Wordley

Transcript & edit : Anne Marie Shin & Neville Sloss

Website guru : Simon Perrin DUOGRAFIK