Max Allen once emailed me and suggested if I was…

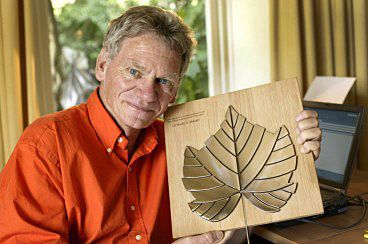

Richard Smart : ‘The flying vine-doctor’

I first heard of Dr Richard Smart one day in New Zealand’s Awatere Valley, in the mid 1990’s.

He was then the New Zealand Government viticultural scientist and had been for many years, since 1981.

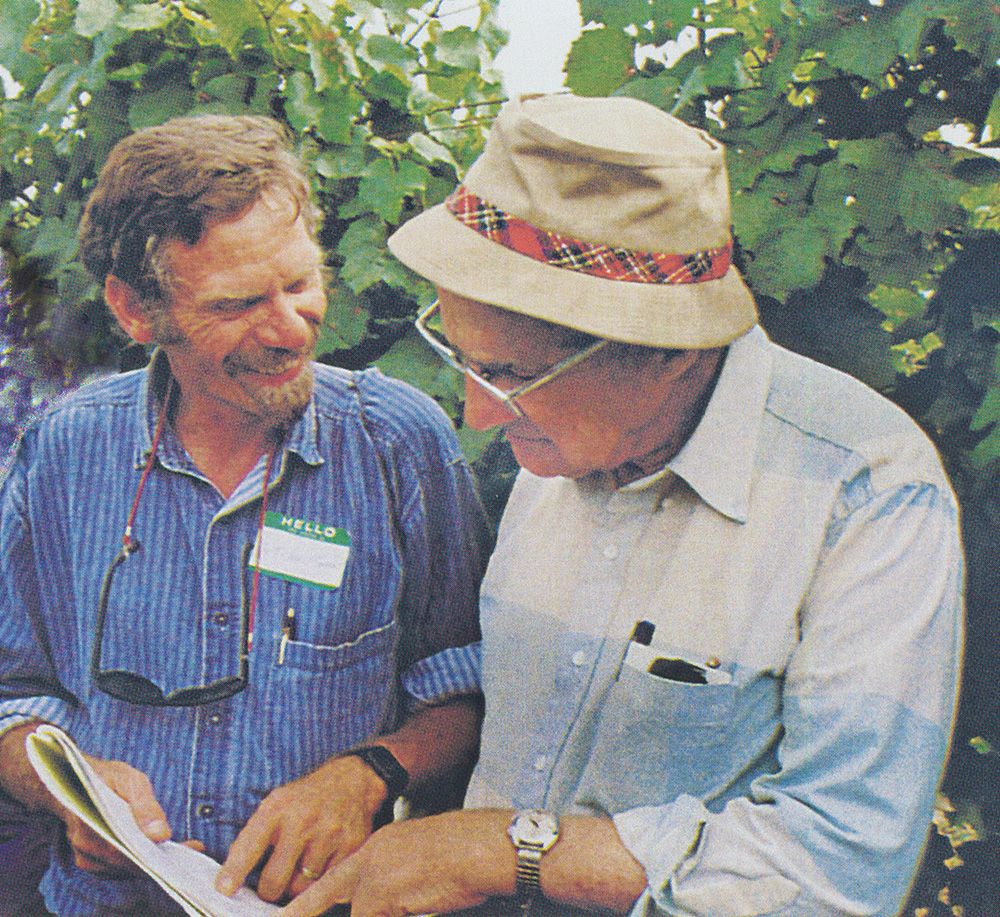

Dr Richard walks the BVE Marananga vineyard with Rob Martyn Delgat’s Group Operations Manager Viticulture & Winemaking : Photo © Milton Wordley

Wikipedia refers to him as a leading global consultant on viticulture methods, who is often referred to as “the flying vine-doctor”.

He is considered responsible for revolutionising grape growing due to his work on canopy management techniques. Richard is now based in Cornwall in the UK. I caught up with him recently in the Barossa Valley where he was consulting at Barossa Valley Estate for the New Zealand wine group ‘Delegat’.

Dr Richard had some very interesting things to say, but one comment in particular struck me,

“ The world’s wine industry in comparison to the world’s agriculture, is the canary in the coal mine because it’s the early warning system. Growing wine grapes is so environmentally sensitive, you only have to look at a wine map of the world to see that. All of those discrete regions with climate benefits to some variety or other. ”

The ‘Flying vine-doctor’. How did you get the name?

The title is self-given but people have called me that now for many years.

It has been common over the last 20 years to use the term “flying winemaker”, they do vintages all over the world. It’s not so common for a viticulturist to do the same.

In January this year, it was my 53rd year in vineyards as a viticulturist, I’m on my fifth passport now, and I really do travel a lot.

You graduated from Sydney University with Honours in Agricultural Science in 1966. Why wine ?

I grew up near Richmond in New South Wales.

Why wine ? It was serendipitous, in many ways. At the time, most of my Uni mates were more clever than I, and they opted for careers in agronomy (field crops and pastures), so I thought I might as well choose something else.

My scholarship provider, NSW Department of Agriculture had a position vacant at Griffith in wine grape research and frankly I knew nothing of grapes, my family didn’t drink wine, and I have never studied viticulture.

I had the opportunity to work there in my university holidays.

I rather liked it, and I particularly liked going to Penfold’s winery and buying flagons of port – they were very cheap.

So anyway, I decided that’s what I’d like to do. So, when I finished University I started work in January 1966.

Early Irrigation trial in Griffith ?

At that time there were issues with red wine quality between the MIA (or Griffith) and the Hunter Valley.

The Hunter industry thought they were making superior wines because they were non-irrigated.

I was responsible for a large-scale trial with Shiraz.

At that time drip irrigation was very new, and so I did some of the first vine experiments with drip irrigation in the world, let alone in Australia.

The big chemical company ICI made some early drip lines which we used, so we compared the non-irrigated with drip irrigation.

In 1970, I won a New South Wales Government Scholarship to Israel to study drip irrigation.

At that time Australia and Israel were doing some of the early research work on irrigation.

I had six months in Israel, I spent a couple of months working at Volcani Research Institute, and then I worked on a kibbutz near the sea of Galilee studying drip irrigation of vineyards.

You did a PHD in the US, what was the subject ?

I returned from Israel via the US. At that time I was interested to do a PhD in the US .

I had done a Masters at Macquarie University while in Griffith, developing a computer model of sunlight interception by vineyards, this was the very early days of computer use in agriculture research.

Most Australian viticulturists studied at the University of California ‘Davis’.

I decided I would do my PhD at Cornell University in upstate New York.

Cornell is one of the top universities in the US, it’s one of the so-called ‘Ivy’ League.

It has a very distinguished School of Agriculture, and my Professor Nelson Shaulis, the father of canopy management.

My research study was done with Concord – a native American variety.

Dr Richard and professor Nelson Shaulis discuss the finer points of canopy assessment Long Island, New York, July 1989.

The winters were ferocious, we had to prune in the snow – I didn’t enjoy that much.

I finished my PhD in 1975, and took up a position at Roseworthy College as a Lecturer in Viticulture.

At that time Roseworthy was trying to lift its game in wine education.

What was your role at Roseworthy ?

I spent four years teaching full-time which I quite enjoyed and then I had a couple of years running a research micro-winery at Roseworthy.

We used to make wines in small-scale.

I did one of my better pieces of research while there and presented it to the University of California Centenary Symposium in 1980.

It was a study on Shiraz , grown in Angle Vale. I made a very simple study of four different canopies that varied in their degree of fruit exposure and shading.

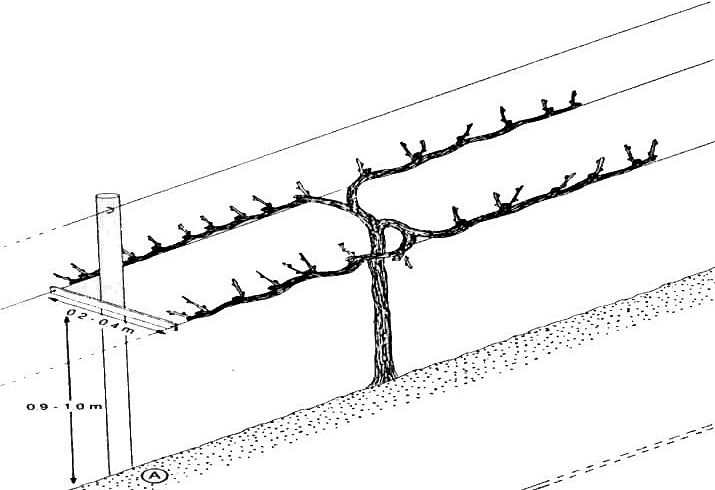

One of my treatments was to ball up the whole canopy with bird netting to make it more shaded, another one was a trellis system that Nelson Shaulis had developed, called the ‘Geneva Double Curtain’, which provided for lots of sun exposure of fruit.

At that time and still to the present, the standard Australian industry response was,

“You don’t want to expose bunches to the sun in the hot climate, in a hot climate they needed to be shaded, they will get sunburnt”.

My research and other’s has shown that the shade of leaves and fruit is very detrimental to grape composition and wine quality and also the yield.

By appropriate canopy management, one can avoid fruit exposure in the hottest part of the day, so even if a few berries show sunburn the fruit will make better wine than if shaded.

GDC training for Gewurztraminer at Te Kauwhata in New Zealand. Note high fruit exposure : Photo © Dr Richard Smart

By avoiding shade in canopies you can improve wine quality even in hot regions.

I proved so in this experiment at least, that the most exposed fruit to sunlight makes the best wine, and the most shaded the worst.

We now understand why, because the UV part of sunlight affects the berries’ skin metabolism and you get more colour, flavour and phenolics; in fact the phenolics content is how the grape bunch protects itself from UV.

So, despite the fruit being more exposed, it’s better for winemaking.

The results we had at that wine tasting were dramatic.

The tasters were winemakers from the Barossa and they thought that the wines with the shaded treatment were from the Riverland and they thought the “unshaded” or wines with more sun exposure to the fruit GDC (Geneva Double Curtain) were cooler climate and better wine !

I mentioned that experiment because it was a theme I’ve worked on for the rest of my life.

When I was at Roseworthy I became good friends with a young French scientist, Alain Carbonneau, who was the same age.

We were the young mavericks of international canopy management research at the time, but following in the footsteps of Shaulis.

While at Roseworthy I bought a 40-acre farm at Williamstown.

There were about 8 acres of vineyards and I was a grower for Orlando Gramps : I planted Chardonnay and Cabernet at a time when they were still novel in the Barossa Valley.

Tell us about your time in New Zealand in the 1980’s.

I was in New Zealand for eight years 1982-1990, as the New Zealand Government viticultural scientist.

I had become very interested in cool climate wines at the time.

This period was at a pivotal stage of the New Zealand wine industry development.

At that time the plantings were just starting in Marlborough.

New Zealand’s Awatere Valley where I first heard of Dr Richard : Photo © Colleen Tunnicliff.

When I first visited there were lots of bare paddocks, you don’t see that now.

I had excellent facilities at my base Ruakura, a famous agricultural research station in Hamilton.

I did lots of research all over New Zealand.

We had a couple of viticultural “bushfires” to put out.

One was phylloxera, a lot of it, as all the plantings were on their own roots, and phylloxera was being spread by the nurseries.

The next had to do with rootstock, we found out that a lot of the planting material was infected with viral disease, and some were mis-named.

So that led to another big part of my work which was to develop a high health collection of vines for use in New Zealand.

We made clonal selections which were virus tested, performed virus elimination and we planted a national collection.

I made a register of all imports before Australia did.

It was important for the subsequent development of New Zealand wines. Part of this work was to make a collection of historic wines imported to New Zealand, because if we could find vines that came out of Europe before 1900 or so, they were more likely to be virus free, because once grafting began in Europe, they unwittingly spread virus diseases which was not known until about 70 years later….

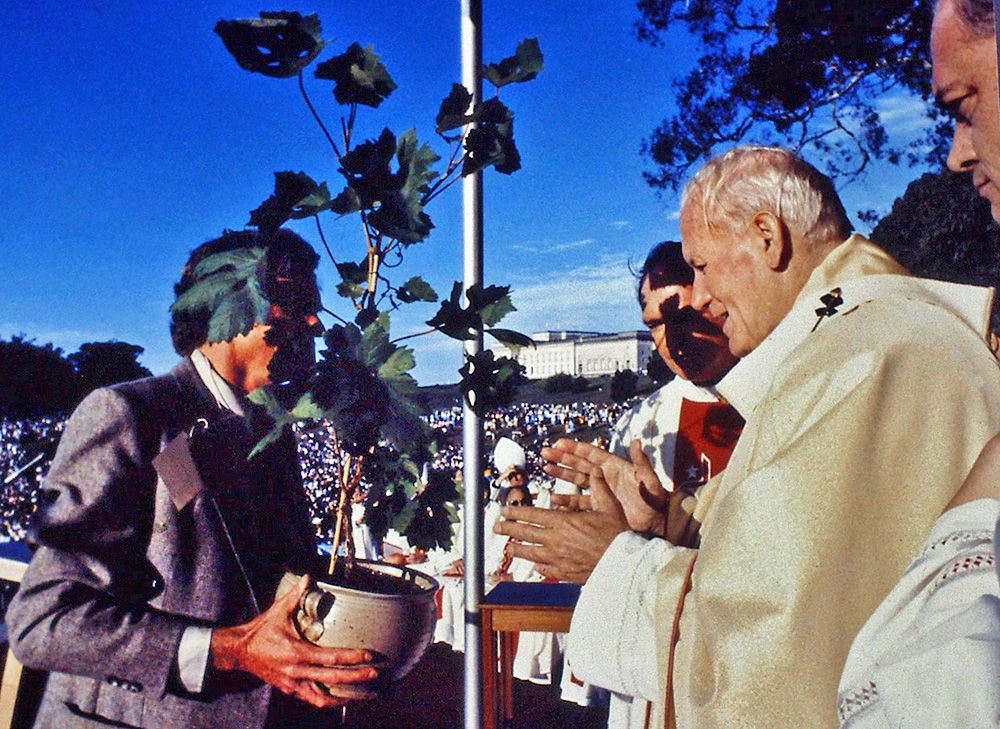

Presenting Pope John Paul with a grapevine originally from one brought to NZ by Catholic missionaries in 1850.

I went to a small Pacific island and took a vine there that had been planted by a French Catholic missionary in 1838.

The priests brought the vine to Futuna Island.

I suspected it was from France, as they were, but it turned out it was a vine that they picked up in Valparaiso, Chile, en route to Futuna.

And that vine was originally brought to South America by the Spanish conquistadors several centuries earlier as a seedling.

This French missionary subsequently became a saint and I presented this Saint’s vine to Pope John Paul in Auckland – it’s a lovely little story.

You are now based in the UK ?

I’ve been living in the UK for seven years.

I’m doing more work in Europe and Asia especially in China.

The growing UK wine sector is, can I say, interesting. The U.K.’s a terrible place to grow grapes, it’s too wet and too cold – we are covering the vines in plastic, to keep them warmer and drier.

The sparkling wines are interesting and gaining recognition, The big problem with UK viticulture is low profitability because of low yields.

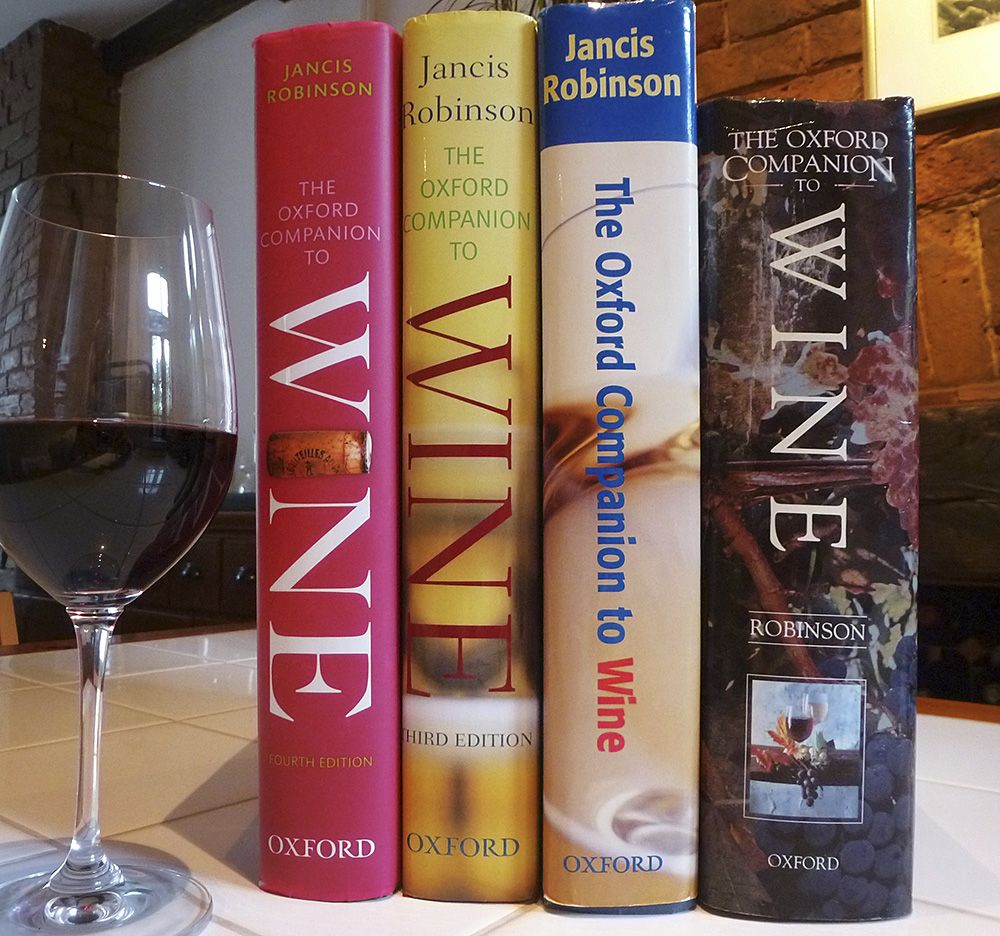

Jancis Robinson ?

I’ve been involved with writing for Jancis Robinson since the days I was in New Zealand, as the first major viticultural contributor then editor of the Oxford Companion of Wine.

It’s been a massive amount of work, not always well paid unfortunately, but anyway I enjoyed the opportunity.

I never imagined as a young man that I might contribute to an Oxford Companion.

Jancis is an extraordinarily gifted writer, with a very sharp mind.

When we worked on the first edition she was having a baby and I got cancer of the mouth !

That was in the late 1980s and we used to communicate by fax, well before email.

But somehow, we did that first edition, and there are now four.

I’ve always thought it important in my career to write articles for publishing in trade magazines designed for growers, as well as scientific publications.

As a scientist you don’t get much recognition for trade publications but they are very important in terms of technology transfer in the industry.

I have written more of these articles than anyone else I know of, in Australia and, NZ, and to a lesser extent in the USA.

Why is canopy management so important ?

Despite having spent most of my career promoting this topic, it sadly remains mostly misunderstood by grape-growers and winemakers.

Were it better understood and applied, then it would result in substantial advances in yield, wine quality and some disease reduction.

This comment applies to vineyards which remain too shaded, as for high vigour situations which are poorly trellised.

Canopy management would be better appreciated and utilised in Australia, if the prevailing attitude in vineyard management was not that of cost reduction rather than profit (or quality) maximisation.

However, I am pleased to say that my book on the subject “Sunlight into Wine” has been a best seller and received an OIV award.

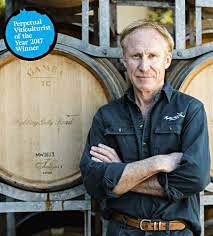

What are you doing in the Barossa ?

I’m consulting at Barossa Valley Estates for BVE’s parent company, the New Zealand wine group ‘Delegat’.

I have a very special relationship with ‘Delegat’, they own the NZ brand Oyster Bay.

I’m told Oyster Bay Sauvignon Blanc is one of the biggest selling white wines in Australia.

How’s that for a NZ company !

I’ve been consulting to them now for many years, they are wonderful clients.

Barossa Valley Estate vineyards : Photo © Dragan Radocaj

During my first visit to Oyster Bay I suggested a trellis system developed by a fellow named Scott Henry, who has now become a friend.

He is a grape grower and winery owner in Oregon.

It was difficult for the ‘Delegat’ vineyard managers to accept my advice, they had heard of the mis-informed comments from other managers, sort of pub talk.

They said, “It won’t work here, too expensive, labour can’t do it, blah blah blah”

My response was firm, I said to them, “Look guys this is rubbish, I know it works I’ve done it so don’t tell me I’m wrong, show me I’m wrong.”

Their boss said, “You heard… give it a go, and do it properly !”

They did small trials and they now have all the vineyards in New Zealand and Australia on the Scott Henry system, why because it works !

They get more yield, better wine and less disease.

‘Delegat’ have the largest area of Scott Henry trellised vineyards in the world.

When ‘Delegat’ bought this place, Barossa Valley Estate, in the Barossa, Jim Delegat said,

“we’ll do the Scott Henry here as well”….

The yield is now double the district average, at eight tons plus to the hectare, for no loss in quality.

How do you see global warming affecting the world of growing grapes and making wine ?

Let me say, I’ve been interested in climate change since the 1970s.

The world’s wine industry, in comparison to the world’s agriculture, is the canary in the coal mine because it’s the early warning system.

I’m of the opinion that the time for doing something about it is now, and the responsibility rests with people like you and I… by that I mean ‘Adults in the western world’.

We need to find a new mindset, we should all be doing something ourselves rather than relying on the government to set the agenda. One of my professors at Cornell, Ed Lemon, first made me aware of the issue. He raised the idea of the effect of increased CO2 in the atmosphere on climate, especially temperature, in a science meeting on campus.

Page grab from a story by Rory Mulholland in the Tele. The caption read : ‘Workers harvest grapes in a vineyard at the chateau les Jonqueyres winemaker, near Bordeaux’.

I was one of the first people in the world to raise awareness about climate change impacts for the wine industry.

I gave a paper to the OIV (World governing body of grapes and wine) General Assembly in around 1988.

I remember there were a bunch of Frenchmen in the room, and they all laughed when I said they may be growing Grenache in Bordeaux in the future.

It is not such a joke now, as new varieties for the region are currently being trialled.

As I’ve often written, the world’s wine industry is going to be one of those most impacted.

Why ? – because of the strong climate by variety interaction of which we are all familiar.

As the climate is going to change we then have to change either regions or varieties.. One of the biggest problems is that we don’t have the appropriate varieties for a warmer Australia right now.

When I was at Roseworthy, I became more interested in climate effects on grapes and wine.

Peter Dry and I and made some early publications, showing the effects of the climate on wine in the Australian wine regions.

It became bleeding obvious to us then that Australia had planted most of its wine grapes in areas that were too hot for quality table wine.

I think there are good opportunities especially in New Zealand and also in Australia to look at newer areas to grow wine grapes…places like Beechworth, Victoria.

I first learnt about Beechworth when I was at Roseworthy.

As part of my climatology class, I gave the students climate data for Bordeaux and asked them to find the closest climate to this in Australia.

One of the areas they came up with was Beechworth.

I remember years ago Peter Dry and I visited Beechworth while we were in the area for a conference in Albury. Nothing growing there then, now I see there’s quite a bit happening.

After a long career at Brown Brothers, Mark Walpole has chosen to plant his own vines there.

In fact, I wonder what the future of many present Australian wine regions may be in a hotter and drier world.

Grape vine trunk diseases ?

Trunk disease TD has been of great concern to me for the last 8 or so years.

I learnt about it in an English vineyard, and since then because I learned to recognize symptoms, I find it everywhere I go, and I mean everywhere; in every country, almost in every vineyard.

Invariably it is not recognised as such, and TD is a problem particularly because of infected plants being produced in the nursery, which happens worldwide

I and others have helped raise the global awareness of the problem at OIV.

And in the Barossa Valley vineyards have been removed around 20 years of age because of trunk disease.

It is so sad – I believe TD will be a bigger problem than phylloxera ever was, and that’s partly because it’s insidious, with hidden symptoms.

New markets : China Asia ?

China is huge. China is amazing.

China is now a huge market for wine from all over the world.

What people don’t think about is China as a wine producer, it’s already the largest producer of things like apples and garlic.

They already have a wine grape area similar to Australia.

If in the future wine production grows like the table grape area has, they may not want so much wine from Australia.

Working on anything new or exciting ?

I must admit I have recently gone over to the “dark side”, and become involved in winemaking research.

I always remember my friend the late Chris Somers of AWRI telling me that “many of the good things the winemakers want in their wine end up on the marc heap”.

I worked with a small-scale research winery at Tamar Ridge in northern Tasmania, evaluating vineyard trials. My colleague and I developed a method to fragment grape skins without damaging seeds.

It produced better and quicker skin extraction, and has proven beneficial to red and white wine quality.

Angela Sparrow made her PhD on the process, and it has been proven now in commercial wineries and led to the development of the recently released Della Toffola DTMA machine.

Australia’s first is at Coriole winery, McLaren Vale.

A French winemaker evaluating the DTMA said “every winery will want one”. I hope so.

In 2018 I was flattered to receive an invitation from Jim Gordon in California to write a piece in the 100 Years collector’s edition of the Wines and Vines magazine, and this was to be the last.

The cover featured the first edition, from December 1, 1919, and discussed preparations for the imminent arrival of Prohibition !

How traumatic that must have been for growers and wineries alike.

I entitled my article “Reflections from a 50-year vineyard meander”.

Among other issues raised I gave tribute to trade journals like Wines and Vines, their role in technology transfer in countries like the USA and Australia, and also to the American Society for Enology and Viticulture, founded in 1950, and model for similar societies in Australia, New Zealand and South Africa.

Anything else you’d like to say ?

I worry about trunk disease, for example the impact on mechanically pruned vines in places like the Barossa, and the relationship to declining yields.

It’s a terrible story and I hold myself partly responsible.

During my time at Roseworthy I was one of the people encouraging and researching mechanical pruning, and mechanical pruning is contributing to trunk disease spread.

I’m embarrassed now to admit that.

I think Australian viticulture went off the rails in the late 1980s and early 1990s, when the industry philosophy was the driven by cost minimization, especially in vineyards. That attitude is more appropriate to a bulk wine industry than a quality one.

Part of it was an attitude that the vineyards were cost centres, they weren’t profit centres.

Dr Richard Smart meets with Drs Roberta De Bei (L) and Cassandra Collins at Adelaide University : Photo © Milton Wordley

Nor was their management acknowledged as primary in wine quality manipulation. The industry focus and marketing continues to be on vinification and winemakers.

Over the next four decades or so, global impacts of climate change will become much more evident, both by increasing temperatures, and by increasing frequency of extreme events, climate chaos I call it.

The global wine sector hopefully will move to do more to avoid this by reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

As an example, CO2 should be captured from fermentations, and glass bottles should be replaced as containers for cheaper, never-to-be-stored wines purchased for immediate consumption.

Glass bottles have a substantial carbon footprint for their manufacture, transport and recycling.

Finally, in a proposal I am pushing for internationally, grapevine prunings can be used as a renewable energy source to replace fossil fuel based energy in wineries, to provide cooling and heating, made possible by European machine development to harvest them economically from the field.

ENDS

Interview, photography & production : Milton Wordley

Edit : Anne-Marie Shin

Website guru : Simon Perrin Version Design